NSA admits to second incident of unauthorized metadata collection

The U.S. National Security Agency scooped up unauthorized call and text message data in October, representing the second such incident known to the public.

An NSA data center in Utah.

The violation was caught by the American Civil Liberties Union through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, according to the Wall Street Journal. Internal NSA memos on the matter are said to have been "heavily" redacted before publishing.

The documents don't indicate how many records were collected, but do say that they came from a telecoms firm who supplied information the NSA didn't ask for, and without sanction by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. The records began arriving on Oct. 3 but only stopped on Oct. 12, when the NSA asked the company to look into the "anomaly."

The ACLU said the documents suggest a person may have been targeted for surveillance as a result of the first violation, which led to the NSA deleting its existing database in June 2018.

The NSA has been collecting phone metadata for years, using it to track terrorism suspects and others. The program was exposed in 2013 by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, showing that many innocent Americans were having data collected as well, potentially making the program a tool for mass surveillance.

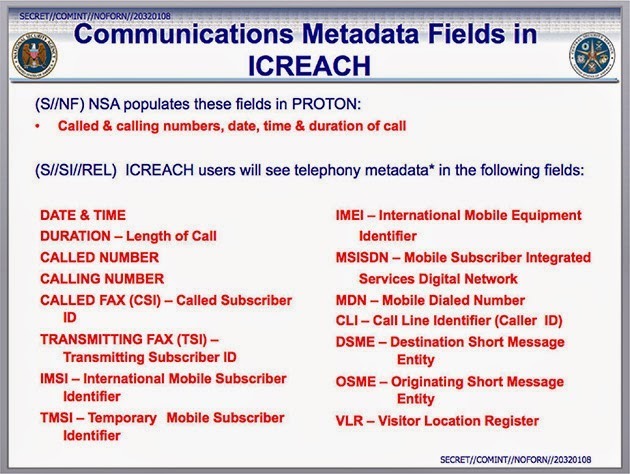

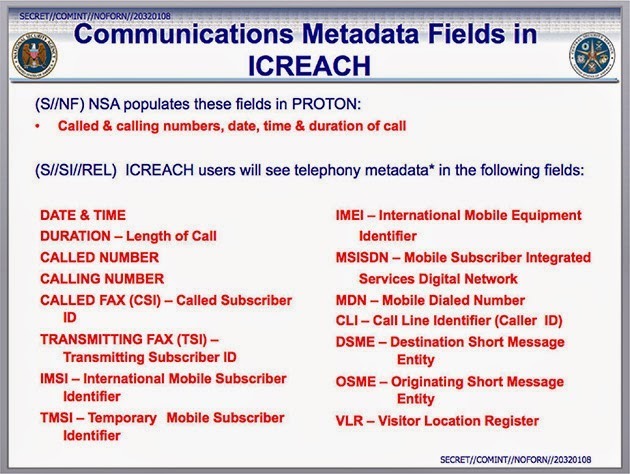

Metadata consists of details like dates, times, phone numbers, and device identifiers. While nominally less invasive than message content, in reality metadata can be used to piece together many details about a person's life, such as daily habits and who their friends and family are.

One of the 2013 documents leaked by Edward Snowden.

2015's U.S.A. Freedom Act scaled back the program, keeping records in the hands of carriers except when requested through court orders. The NSA's internal records did drop dramatically, although as recently as 2017, it had 534 million records and just 40 targets.

That database was allegedly deleted in response to glitches causing carriers to send logs with both accurate and inaccurate information. That was blamed for gathering data on people unconnected to targets, at which point the NSA decided it would be easier to start over rather than do narrow scrubbing.

The Freedom Act is due to expire at the end of 2019, and the Trump administration will have to push for renewal legislation if it wants it. In March an advisor for Republican Rep. Kevin McCarthy of California claimed that the NSA hadn't been using the metadata collection system for six months, but that may conflict with news of the October incident.

Apple CEO Tim Cook became involved in the NSA controversy after Snowden's revelations, meeting with President Obama and putting pressure on Congress. The company eventually began disclosing government data requests, if only in the vague manner allowed by U.S. law.

Less is known about the state of PRISM, an NSA program collecting data from internet-based tech companies. Following the Snowden leaks, Apple insisted that it had "never heard of PRISM" and didn't "provide any government agency with direct access to our servers," despite that sort of access being mentioned in leaked NSA briefing documents.

An NSA data center in Utah.

The violation was caught by the American Civil Liberties Union through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, according to the Wall Street Journal. Internal NSA memos on the matter are said to have been "heavily" redacted before publishing.

The documents don't indicate how many records were collected, but do say that they came from a telecoms firm who supplied information the NSA didn't ask for, and without sanction by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. The records began arriving on Oct. 3 but only stopped on Oct. 12, when the NSA asked the company to look into the "anomaly."

The ACLU said the documents suggest a person may have been targeted for surveillance as a result of the first violation, which led to the NSA deleting its existing database in June 2018.

The NSA has been collecting phone metadata for years, using it to track terrorism suspects and others. The program was exposed in 2013 by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, showing that many innocent Americans were having data collected as well, potentially making the program a tool for mass surveillance.

Metadata consists of details like dates, times, phone numbers, and device identifiers. While nominally less invasive than message content, in reality metadata can be used to piece together many details about a person's life, such as daily habits and who their friends and family are.

One of the 2013 documents leaked by Edward Snowden.

2015's U.S.A. Freedom Act scaled back the program, keeping records in the hands of carriers except when requested through court orders. The NSA's internal records did drop dramatically, although as recently as 2017, it had 534 million records and just 40 targets.

That database was allegedly deleted in response to glitches causing carriers to send logs with both accurate and inaccurate information. That was blamed for gathering data on people unconnected to targets, at which point the NSA decided it would be easier to start over rather than do narrow scrubbing.

The Freedom Act is due to expire at the end of 2019, and the Trump administration will have to push for renewal legislation if it wants it. In March an advisor for Republican Rep. Kevin McCarthy of California claimed that the NSA hadn't been using the metadata collection system for six months, but that may conflict with news of the October incident.

Apple CEO Tim Cook became involved in the NSA controversy after Snowden's revelations, meeting with President Obama and putting pressure on Congress. The company eventually began disclosing government data requests, if only in the vague manner allowed by U.S. law.

Less is known about the state of PRISM, an NSA program collecting data from internet-based tech companies. Following the Snowden leaks, Apple insisted that it had "never heard of PRISM" and didn't "provide any government agency with direct access to our servers," despite that sort of access being mentioned in leaked NSA briefing documents.

Comments

Google allowed the NSA to contribute code on Android. Of course they later had excuses as to why.

Without programs like this?