How Apple dodged the flop of Android's headset VR

Between 2014 and 2019, Google and its Android licensees promoted various smartphone-based virtual reality systems. At the same time, Apple remained conspicuously absent from the smartphone VR headset race, which in hindsight appears prescient. Here's a look at why.

Attaching a phone to a VR headset ended up as a major commercial failure

By 2014, Apple's five-year-old iPad was reaching its peak unit sales. Tablets from Microsoft, as well as a series of Android tablets from Google and its licensees, were all failing to find similar interest among buyers.

The smartphone market also seemed to be maturing, with increasingly bleak prospects for new entrants, as demonstrated by notable failures ranging from Amazon's Fire Phone to more than one Facebook Phone flop. The timing seemed right for a new leap into a fresh category smart devices in an area Apple hadn't already dominated.

Samsung had just launched its Galaxy Gear watch the previous fall, beating Apple and others into the wearables market. And at I/O 2014, Google was floating out Cardboard, an experimental new platform for Virtual Reality. It fitted a smartphone across the user's face, working as a simple, low-cost way to experiment with VR in the form of a handset-headset.

Just a few months later, Samsung announced a more sophisticated VR headset: Gear VR, which was custom-designed to work with Samsung's flagship phones, rather than the general-purpose, nearly free experiment of Cardboard. Samsung developed Gear VR in partnership with Oculus Rift, which was then a two-year-old startup working on a dedicated VR headset intended to be tethered to a powerful PC.

Facebook had just acquired Oculus for $2 billion, suggesting lots of potential for VR in general and exciting synergy between the popular social network and the word's leading hardware maker. Facebook appeared to expect that Samsung's Gear VR would create a high volume, lower quality mobile entry to the headset VR market it planned to own on the premium end with dedicated Oculus headsets powered by a desktop PC.

Samsung similarly boasted of shipping 5 million Gear VR headsets by early 2017. Yet that announcement came after an embarrassing crisis with Galaxy Note 7, the company's phablet that was intended to push Gear VR adoption but which instead had a tendency to burst into flames due to its flawed battery design. The idea of a face-mounted exploding smartphone dashed Samsung's big push and derailed momentum for the device that was supposed to bring Gear VR into the mainstream.

While the meltdown of Galaxy Note 7 sure didn't help, handset VR was failing to find real adoption that lived beyond just an initial curiosity. Even at the end of 2016, pundits were declaring that VR had become the "biggest loser" of the year despite strident efforts by Google, Samsung, and many others to promote VR as the next big thing.

Google put significant effort into Daydream VR, then woke up and forgot about it

Across 2017 Google promoted the second generation of its Daydream VR platform and its chief executive Sundar Pichai anticipated nearly a dozen Android smartphones supporting it by the end of the year, including Google's Pixel 2. Daydream was supposed to help sell premium Android phones, but it simply wasn't.

The next year, Google worked with Lenovo to launch a standalone Mirage Solo headset capable of running Daydream, but that didn't draw sufficient interest either. By 2019, Google was ready to discontinue the entire Daydream VR project as content partners backed way and audiences failed to materialize.

In August 2019, Samsung launched its new Galaxy Note 10 without any support for Gear VR, then pulled Gear VR itself off the market. Oculus' chief technology officer John Carmack gave a "eulogy" for Gear VR, saying that while Samsung shipped lots of units-- much larger than all of Oculus' dedicated VR headsets-- it wasn't successfully retaining the interest of users. Carmack admitted spending lots of money on content for Gear VR that failed to gain any traction.

Samsung has now abandoned its own XR video service, suggesting a total end to any further interest in Gear VR as a platform. Google similarly dropped Daydream support from its budget-priced Pixel 3a last year and ignored its VR platform entirely when it launched Pixel 4-- which itself was running into an existential crisis.

Historically, some features come and go. Both PDAs and iPods achieved popularity for about five solid years before giving way to smartphones, but their features lived on within phones. Phone-based VR never grew into much more than a promotional effort. Samsung effectively gave Gear VR away until it stopped making sense to continuing losing money on it. PC and console-based VR systems such as the HTC Vibe and various products from Oculus have found an audience, but it appears VR phone headsets have gone the way of 3D mobile displays.

All the investment by Google, Samsung, Facebook, and many others into headset Android VR has turned into a miserable failure on par with Android tablets, Chrome OS Pixel netbooks, Android's Wear OS, and other initiatives that just couldn't gain sufficient traction to stay in business.

Samsung wanted to differentiate its Galaxy brand from other Android phones, rising above pure commodity. Among handset makers, Samsung invested the most in Android VR because it had the most to gain. It had its high-end OLED displays; wanted to sell higher-end, larger phones with less competition from other Android makers; and it sought to produce original VR content it could sell to its Galaxy customers.

Yet Samsung's race to deliver its Galaxy Gear VR platform neglected to consider whether it made any sense to dedicate one's phone to headset VR sessions, given that while using it in a headset, it would not be accessible to normal apps, nor could be used as a phone, messaging device, camera, and so on. Using a phone to power a VR headset was also computationally intensive, resulting in mobile overheating issues as well as rapidly draining the battery.

Carmack explained that one of the largest issues was getting users to peel the case off their phone and plug it into the Gear VR handset, a "friction" that made it too clumsy for most users to want to try out VR more than a couple times.

Facebook's Oculus put significant resources into Gear VR before giving up

There were also predictions Apple would soon be following everyone else into the market. Writing for Forbes, as apparently anyone can, Evan Spence claimed to "reveal" a "New iPhone VR Headset Plan based on patents Apple had filed. Piper Jaffray's Gene Munster, having tired of predicting an Apple TV set that never arrived, decided to switch things up and declare that he expected Apple to ship a VR headset by 2017.

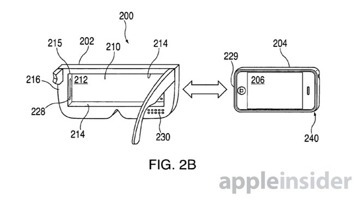

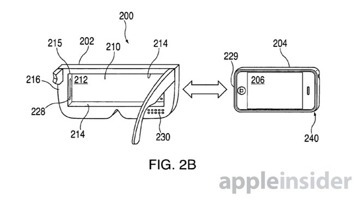

Apple has patented many concepts it never subsequently released as products

Yet those predictions failed to materialize. We know that Apple had explored VR headsets internally. It patented various aspects of VR that could be delivered as a phone-based headset. Those conceptual drawings inspired pundits and analysts to dream up predictions that if Apple were thinking about it, it was also doing it.

But, we also know Apple is famous for "saying no," as part of the culture that Steve Jobs defined. Unlike many others in the tech industry, Jobs recognized that Apple couldn't be good at everything and needed to focus. This focus may likely have led Apple into concluding well in advance that phone-headset VR wouldn't work well, for the various reasons Carmack described in hindsight. Apple was certainly already aware of the challenges facing its mobile devices in terms of thermal envelope and battery duration.

Apple had just shown similar restraint in launching Apple Watch in 2015, refusing to gild the lily by adding a low quality, purposeless camera the way Samsung had on its Galaxy Gear or entertaining the frivolity of Google in insisting that a smartwatch should be round, even though this would greatly reduce the value of the product. Apple Watch, along with iPad before it, were both simple and almost effortless to use, with loads of expected complexity purposely pared off and thrown away.

But beyond just "choosing not to launch" a VR headset, Apple also didn't need to. By 2015, it had delivered Apple Watch and was seeing significant premium-priced wearable adoption, despite the market having been flooded for years with much cheaper smartwatch bands-- including the never very successful Galaxy Gear. Apple was also making billions in sales of iPad, despite the appearance that the tablet market was in decline. It had also just launched iPhone 6 to wild acclaim, boosting its phone sales into a new tier above 200 million units annually.

Apple wasn't facing any need to stand out against Android 7 in terms of exciting technology features. It wasn't trying to prop up a premium-priced brand with flagging sales like Samsung's Galaxy. Apple had three massive recent hits that were still performing very well, and it was planning its next hardware hits for the future.

It didn't need to float out an experimental DIY kit like Cardboard, which Google itself did for iPhone, in an attempt to gain some traction. Apple also didn't need to distract itself with a new hardware product that would take up significant resources that could be instead applied to more successful ideas.

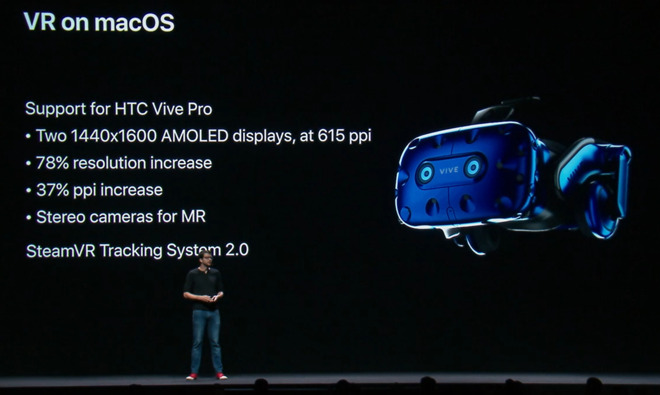

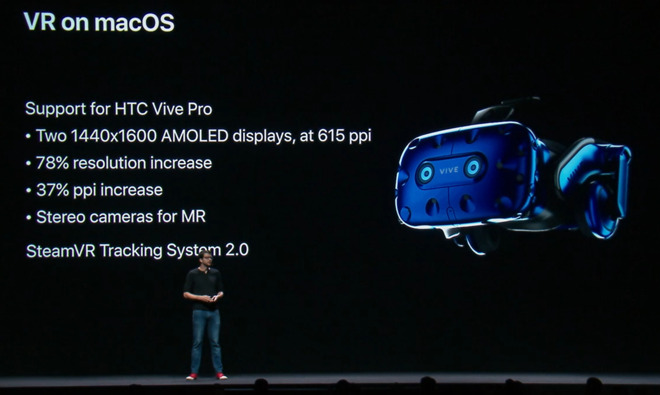

Apple launched support for non-phone VR headsets in macOS at WWDC18

Rather than trying to squeeze entry-level VR out of mobile phones, Apple announced support for HTC's Vive Pro standalone headset on its desktop macOS Mojave platform, an initiative aimed at developing content for VR experiences. Even that didn't happen until WWDC18, two solid years after headset VR was first paraded around the tech media as the "exciting new thing" that Apple was "clearly behind" in.

There's another reason why Apple wasn't focused on virtual reality, as the next segment will examine.

Attaching a phone to a VR headset ended up as a major commercial failure

The early promise of smartphone VR

Five years ago, many assumed that headset VR could be the next big thing in mobile devices. Apple had introduced the iPhone as the first modern smartphone in 2007. Building on that, it then redefined the concept of tablets with the iPad in 2010.By 2014, Apple's five-year-old iPad was reaching its peak unit sales. Tablets from Microsoft, as well as a series of Android tablets from Google and its licensees, were all failing to find similar interest among buyers.

The smartphone market also seemed to be maturing, with increasingly bleak prospects for new entrants, as demonstrated by notable failures ranging from Amazon's Fire Phone to more than one Facebook Phone flop. The timing seemed right for a new leap into a fresh category smart devices in an area Apple hadn't already dominated.

Samsung had just launched its Galaxy Gear watch the previous fall, beating Apple and others into the wearables market. And at I/O 2014, Google was floating out Cardboard, an experimental new platform for Virtual Reality. It fitted a smartphone across the user's face, working as a simple, low-cost way to experiment with VR in the form of a handset-headset.

Just a few months later, Samsung announced a more sophisticated VR headset: Gear VR, which was custom-designed to work with Samsung's flagship phones, rather than the general-purpose, nearly free experiment of Cardboard. Samsung developed Gear VR in partnership with Oculus Rift, which was then a two-year-old startup working on a dedicated VR headset intended to be tethered to a powerful PC.

Facebook had just acquired Oculus for $2 billion, suggesting lots of potential for VR in general and exciting synergy between the popular social network and the word's leading hardware maker. Facebook appeared to expect that Samsung's Gear VR would create a high volume, lower quality mobile entry to the headset VR market it planned to own on the premium end with dedicated Oculus headsets powered by a desktop PC.

Five year fad of Android VR

By 2016, Google announced having shipped five million Cardboard viewers. By the end of that year, Google upgraded Cardboard into Daydream, which integrated handset VR support directly into the OS with Android 7.1 Nougat. Daydream raised its minimum specifications to require Google's Pixel, a Motorola Z, Huawei Mate 9, Samsung Galaxy S8, or a similar flagship-class Android phone. Google shipped VR-enabled versions of its Maps, Photos, YouTube, and Google Play Movies and worked to line up partners producing mobile VR experiences.Samsung similarly boasted of shipping 5 million Gear VR headsets by early 2017. Yet that announcement came after an embarrassing crisis with Galaxy Note 7, the company's phablet that was intended to push Gear VR adoption but which instead had a tendency to burst into flames due to its flawed battery design. The idea of a face-mounted exploding smartphone dashed Samsung's big push and derailed momentum for the device that was supposed to bring Gear VR into the mainstream.

While the meltdown of Galaxy Note 7 sure didn't help, handset VR was failing to find real adoption that lived beyond just an initial curiosity. Even at the end of 2016, pundits were declaring that VR had become the "biggest loser" of the year despite strident efforts by Google, Samsung, and many others to promote VR as the next big thing.

Google put significant effort into Daydream VR, then woke up and forgot about it

Across 2017 Google promoted the second generation of its Daydream VR platform and its chief executive Sundar Pichai anticipated nearly a dozen Android smartphones supporting it by the end of the year, including Google's Pixel 2. Daydream was supposed to help sell premium Android phones, but it simply wasn't.

The next year, Google worked with Lenovo to launch a standalone Mirage Solo headset capable of running Daydream, but that didn't draw sufficient interest either. By 2019, Google was ready to discontinue the entire Daydream VR project as content partners backed way and audiences failed to materialize.

In August 2019, Samsung launched its new Galaxy Note 10 without any support for Gear VR, then pulled Gear VR itself off the market. Oculus' chief technology officer John Carmack gave a "eulogy" for Gear VR, saying that while Samsung shipped lots of units-- much larger than all of Oculus' dedicated VR headsets-- it wasn't successfully retaining the interest of users. Carmack admitted spending lots of money on content for Gear VR that failed to gain any traction.

Samsung has now abandoned its own XR video service, suggesting a total end to any further interest in Gear VR as a platform. Google similarly dropped Daydream support from its budget-priced Pixel 3a last year and ignored its VR platform entirely when it launched Pixel 4-- which itself was running into an existential crisis.

Historically, some features come and go. Both PDAs and iPods achieved popularity for about five solid years before giving way to smartphones, but their features lived on within phones. Phone-based VR never grew into much more than a promotional effort. Samsung effectively gave Gear VR away until it stopped making sense to continuing losing money on it. PC and console-based VR systems such as the HTC Vibe and various products from Oculus have found an audience, but it appears VR phone headsets have gone the way of 3D mobile displays.

All the investment by Google, Samsung, Facebook, and many others into headset Android VR has turned into a miserable failure on par with Android tablets, Chrome OS Pixel netbooks, Android's Wear OS, and other initiatives that just couldn't gain sufficient traction to stay in business.

Why Android VR flopped

Mobile VR seemed to make sense: why not use the relatively expensive smartphone many people already had to deliver decent quality VR, using a moderately priced electronic headset such as Samsung's Gear VR, or a simple passive box like Google's Cardboard or Daydream initiatives? For phone manufacturers, VR seemed like an easy way to sell customers on a fancier phone with a nicer screen. For Google, it was also a way to attract attention to Android as a platform.Samsung wanted to differentiate its Galaxy brand from other Android phones, rising above pure commodity. Among handset makers, Samsung invested the most in Android VR because it had the most to gain. It had its high-end OLED displays; wanted to sell higher-end, larger phones with less competition from other Android makers; and it sought to produce original VR content it could sell to its Galaxy customers.

Yet Samsung's race to deliver its Galaxy Gear VR platform neglected to consider whether it made any sense to dedicate one's phone to headset VR sessions, given that while using it in a headset, it would not be accessible to normal apps, nor could be used as a phone, messaging device, camera, and so on. Using a phone to power a VR headset was also computationally intensive, resulting in mobile overheating issues as well as rapidly draining the battery.

Carmack explained that one of the largest issues was getting users to peel the case off their phone and plug it into the Gear VR handset, a "friction" that made it too clumsy for most users to want to try out VR more than a couple times.

Facebook's Oculus put significant resources into Gear VR before giving up

Why Apple didn't launch its own VR headset

Across 2016, Apple was saddled with a media narrative that relentlessly claimed the upcoming iPhone 7 would be "boring," with various proponents complaining in particular that Apple wasn't doing anything interesting in VR the way Google, Facebook, and Samsung publicly were.There were also predictions Apple would soon be following everyone else into the market. Writing for Forbes, as apparently anyone can, Evan Spence claimed to "reveal" a "New iPhone VR Headset Plan based on patents Apple had filed. Piper Jaffray's Gene Munster, having tired of predicting an Apple TV set that never arrived, decided to switch things up and declare that he expected Apple to ship a VR headset by 2017.

Apple has patented many concepts it never subsequently released as products

Yet those predictions failed to materialize. We know that Apple had explored VR headsets internally. It patented various aspects of VR that could be delivered as a phone-based headset. Those conceptual drawings inspired pundits and analysts to dream up predictions that if Apple were thinking about it, it was also doing it.

But, we also know Apple is famous for "saying no," as part of the culture that Steve Jobs defined. Unlike many others in the tech industry, Jobs recognized that Apple couldn't be good at everything and needed to focus. This focus may likely have led Apple into concluding well in advance that phone-headset VR wouldn't work well, for the various reasons Carmack described in hindsight. Apple was certainly already aware of the challenges facing its mobile devices in terms of thermal envelope and battery duration.

Apple had just shown similar restraint in launching Apple Watch in 2015, refusing to gild the lily by adding a low quality, purposeless camera the way Samsung had on its Galaxy Gear or entertaining the frivolity of Google in insisting that a smartwatch should be round, even though this would greatly reduce the value of the product. Apple Watch, along with iPad before it, were both simple and almost effortless to use, with loads of expected complexity purposely pared off and thrown away.

But beyond just "choosing not to launch" a VR headset, Apple also didn't need to. By 2015, it had delivered Apple Watch and was seeing significant premium-priced wearable adoption, despite the market having been flooded for years with much cheaper smartwatch bands-- including the never very successful Galaxy Gear. Apple was also making billions in sales of iPad, despite the appearance that the tablet market was in decline. It had also just launched iPhone 6 to wild acclaim, boosting its phone sales into a new tier above 200 million units annually.

Apple wasn't facing any need to stand out against Android 7 in terms of exciting technology features. It wasn't trying to prop up a premium-priced brand with flagging sales like Samsung's Galaxy. Apple had three massive recent hits that were still performing very well, and it was planning its next hardware hits for the future.

It didn't need to float out an experimental DIY kit like Cardboard, which Google itself did for iPhone, in an attempt to gain some traction. Apple also didn't need to distract itself with a new hardware product that would take up significant resources that could be instead applied to more successful ideas.

Apple launched support for non-phone VR headsets in macOS at WWDC18

Rather than trying to squeeze entry-level VR out of mobile phones, Apple announced support for HTC's Vive Pro standalone headset on its desktop macOS Mojave platform, an initiative aimed at developing content for VR experiences. Even that didn't happen until WWDC18, two solid years after headset VR was first paraded around the tech media as the "exciting new thing" that Apple was "clearly behind" in.

There's another reason why Apple wasn't focused on virtual reality, as the next segment will examine.

Comments

I kind of feel like AR is heading the same way. Apple added it in and started pushing a couple of years ago but I’ve yet to see any real use for it or to see it take off, either. It may be that AR is for Apple what VR was for Samsung.

The Newton had a significant number of orders for vertical applications that were never fulfilled once it was effectively killed. We will never know if it could have been successful if Apple hadn’t stopped its development. On the other hand, having stopped the Newton, Jobs laid the path for iOS and iPadOS. If the Newton OS had remained viable, perhaps that doesn’t happen and Apple would not be the same company today.

Kinda like how you're reacting to Google Glass and AR when neither are even mentioned in this article?

the fact that VR has found a niche use in gaming doesn’t change the fact that it is not a must-have feature for smart phones.

Thanks for trying to summarize the article, but Oculus did "come to mobile," in the form of Gear VR. Listen to Carmack talk about it. There's a link in the article.

Newton was on the market for solidly five years. Apple licensed its tech to Motorola and others. It was clear that it wasn't going to fly. Anything you could do with Newton could be done with Palm or WinCE with less money and more third party support. By 1998 investing more into Newton was like investing more into QuickDraw 3D or the Dylan language.