APHL partners with Apple, Google and Microsoft on national COVID-19 Exposure Notification ...

The Association of Public Health Laboratories is working with Apple, Google and Microsoft to build a national server that will securely store COVID-19 Exposure Notification data, a system that promises to bolster state and regional efforts to contain the virus.

Detailed in a blog post Friday, the project aims to develop a more comprehensive and cohesive exposure notification solution for the U.S.

Instead of storing user contact tracing keys -- critical, time-sensitive information -- on multiple, unlinked servers run by state agencies, APHL offers to securely compile and make that information available on a national server. Storing keys of affected users on a single database eliminates duplication and can enable notifications across state borders, the group said. Further, states and territorial agencies that integrate with APHL's proposed server would be able to more rapidly build out exposure notification apps.

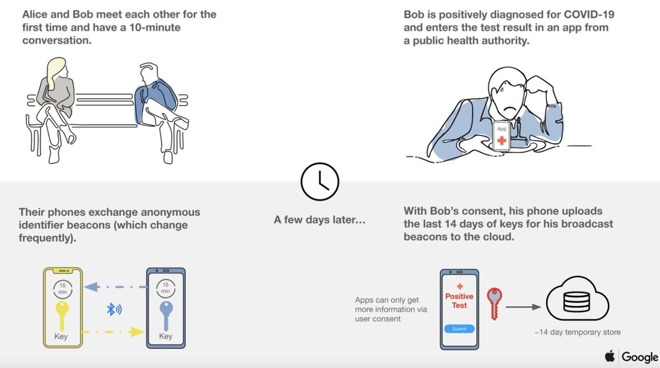

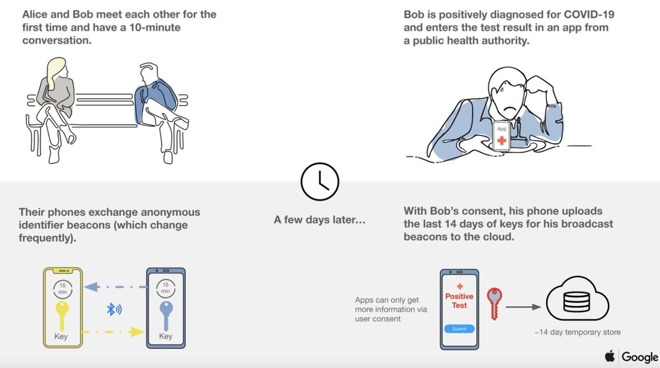

The system implements Apple and Google's Exposure Notification API, which uses random device identifiers -- keys -- to generate temporary IDs that are sent between devices via close proximity Bluetooth communications. By swapping keys, apps integrating the Apple-Google system can track and notify users when they are exposed to others who test positive for coronavirus.

With security at the fore, the solution does not store data on central servers run by Apple or Google, but instead silos anonymized Bluetooth beacons on user devices until participants elect to share the information with an outside party. If and when a user is diagnosed with COVID-19, they can opt to upload a 14-day list of recent anonymized contacts to a distribution server, which matches beacon IDs and sends out notifications alerting those individuals that they came in close contact with a carrier of the virus. Doctors can also peruse the data, if such access is granted.

Those protections extend to the APHL initiative.

While not specifically outlined in today's announcement, APHL would likely take over the role of providing a contact distribution server, in this case for the entirety of America. Microsoft is partnering on the project to provide the national cloud-based key server based on an open source design created by Google Cloud.

"We're honored to partner with Apple, Google and Microsoft to make this groundbreaking technology accessible to state and territorial public health agencies," said Bill Whitmar, president of APHL and director of the Missouri State Public Health Laboratory. "Apps using this technology will rapidly inform users of a potential exposure to COVID-19 and provide them information they can use to protect themselves and their families."

APHL has extensive experience in connecting public health laboratories, entities and government agencies. The group's Public Health Laboratory Interoperability Project launched in 2006 as one of the first systems to allow for the exchange of standardized data between public health entities. That was followed by APHL Informatics Messaging Services, which has evolved from a one-way conveyance of critical health data to a cloud-based platform that "transports, translates, validates and hosts data for federal, state and local public health agencies," according to the post.

Exposure notification technology shows promise, though adoption needs to reach critical mass in any given population before it becomes an effective tool in staunching the coronavirus tide. So far, only a handful of countries have launched apps that integrate the API. No U.S. states have followed suit, though three -- Alabama, North Dakota and South Carolina -- have signaled intent to do so amid a resurgence in cases across the country.

Detailed in a blog post Friday, the project aims to develop a more comprehensive and cohesive exposure notification solution for the U.S.

Instead of storing user contact tracing keys -- critical, time-sensitive information -- on multiple, unlinked servers run by state agencies, APHL offers to securely compile and make that information available on a national server. Storing keys of affected users on a single database eliminates duplication and can enable notifications across state borders, the group said. Further, states and territorial agencies that integrate with APHL's proposed server would be able to more rapidly build out exposure notification apps.

The system implements Apple and Google's Exposure Notification API, which uses random device identifiers -- keys -- to generate temporary IDs that are sent between devices via close proximity Bluetooth communications. By swapping keys, apps integrating the Apple-Google system can track and notify users when they are exposed to others who test positive for coronavirus.

With security at the fore, the solution does not store data on central servers run by Apple or Google, but instead silos anonymized Bluetooth beacons on user devices until participants elect to share the information with an outside party. If and when a user is diagnosed with COVID-19, they can opt to upload a 14-day list of recent anonymized contacts to a distribution server, which matches beacon IDs and sends out notifications alerting those individuals that they came in close contact with a carrier of the virus. Doctors can also peruse the data, if such access is granted.

Those protections extend to the APHL initiative.

While not specifically outlined in today's announcement, APHL would likely take over the role of providing a contact distribution server, in this case for the entirety of America. Microsoft is partnering on the project to provide the national cloud-based key server based on an open source design created by Google Cloud.

"We're honored to partner with Apple, Google and Microsoft to make this groundbreaking technology accessible to state and territorial public health agencies," said Bill Whitmar, president of APHL and director of the Missouri State Public Health Laboratory. "Apps using this technology will rapidly inform users of a potential exposure to COVID-19 and provide them information they can use to protect themselves and their families."

APHL has extensive experience in connecting public health laboratories, entities and government agencies. The group's Public Health Laboratory Interoperability Project launched in 2006 as one of the first systems to allow for the exchange of standardized data between public health entities. That was followed by APHL Informatics Messaging Services, which has evolved from a one-way conveyance of critical health data to a cloud-based platform that "transports, translates, validates and hosts data for federal, state and local public health agencies," according to the post.

Exposure notification technology shows promise, though adoption needs to reach critical mass in any given population before it becomes an effective tool in staunching the coronavirus tide. So far, only a handful of countries have launched apps that integrate the API. No U.S. states have followed suit, though three -- Alabama, North Dakota and South Carolina -- have signaled intent to do so amid a resurgence in cases across the country.

Comments

It may be a prepackaged solution for the next pandemic though.

Having said that, I have a few co-workers who had a knee jerk reaction when they saw the API in the iOS update last month. They clearly didn't understand the methodology or privacy protections built in to the system.

This idea to have a centralized repository though...no. It violates the core principle of the G/A system. The whole essence of it is to be secure because there is no data on a central server that WILL be hacked, or receive a warrant to trace people.

So yes to the app.

No the this though.

As indicated by previous individuals, anyone with a cellphone is continually sharing identity and position in order for the phone to function. This protocol shares neither identity nor position. It is just about notification of possible exposure and thus is much more privacy protective than the billions of cellphones in use.

That's just the US, warts and all. It is certainly not a place for everyone, not a place where people just fall in line, it's what it is.

This is the fragmentation you Apple haters wanted. Now you got it.

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/can-kids-spread-the-coronavirus-conclusively-without-a-doubt-e2-80-93-yes-experts-say/ar-BB16QSYT

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-23/school-children-don-t-spread-coronavirus-french-study-shows

Tracing people can help with easing the lockdowns as it could flag an outbreak and allow locking down regions instead of countries but it needs active participation to be effective and for people to update their mobile devices. The slowest part for tracing will be getting a test to confirm infection. There was a trial of a tracing app that had positive uptake:

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8525395/Test-Trace-DID-work-Isle-Wight-study-finds.html

It was on an island, which is easier to control and there were other factors involved but it must have helped with some cases. They mentioned not being able to track distance very well. Bluetooth has a range of up to 100 metres and some apps warn people if they've come within 100m of anywhere with an infection:

https://qz.com/1810651/south-koreans-are-using-smartphone-apps-to-avoid-coronavirus/

I guess it's safer to be overly cautious but trains at a station with 300+ people each would be in proximity of someone on the platform who might never get on the same train. The documents say there are measures available for exposure time and signal attenuation:

https://www.apple.com/covid19/contacttracing/

The app developers will need to do some tuning to get the best results. Since millions are already infected, that's a lot of already untraced contact points. It's worth trying everything to help ease the spread and to get more information about how and where it spreads but it ultimately needs immunity. When the cold/flu season starts, people aren't going to know what they have.

People use centralized services all the time. iTunes/App Store/iCloud/Apple TV/Google Play/GMail/Amazon/eBay are all centralized services. What's important is what they are storing about you, not that they are storing information. A central server needs to be used for notifications, Apple and Google describe how people need to set it up:

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/exposurenotification/setting_up_an_exposure_notification_server

https://github.com/google/exposure-notifications-server

Devices don't send out notifications peer-to-peer, the apps routinely query the notification server for reported infections for matches with the device's keys. All tracing methods require some compromises to user privacy as the notification server can track a request IP and the apps can report the match to the server but a random app from the App Store can do worse than this (Safari's reader feature can let you bypass the paywall if it pops up):

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/12/10/business/location-data-privacy-apps.html

Also remember that the core principle of the AGEN was to not store every token and particularly no location. This does neither and in fact they wanted to restrict it to one app per country anyway, excluding the US. So this falls in line with the original principle.

They've discovered that 8.8% who tested positive had experienced a skin rash, compared to 5.4% who tested negative. Similarly, 8.2% of users who tested negative but also had Covid symptoms reported having a rash. A followup study of 12,000 showed 17% testing positive had a rash as the first symptom, and 21% who tested positive had a rash as the only symptom.

Thus, the UK study seems to have decently confirmed that a rash is one of the symptoms of Covid.

This illustrates the value using apps.