How Apple's use of eucalyptus in Apple 2030 is controversial

Apple invests quite a bit of time, money, and effort into its environmental initiatives, but it's hard to see whether or not its efforts are making an impact.

Eucalyptus trees | Image credit: ekaterinvor on Pixabay

The saying goes, "the road to hell is paved with good intentions." It's very possible to do a lot of harm while attempting to do a lot of good.

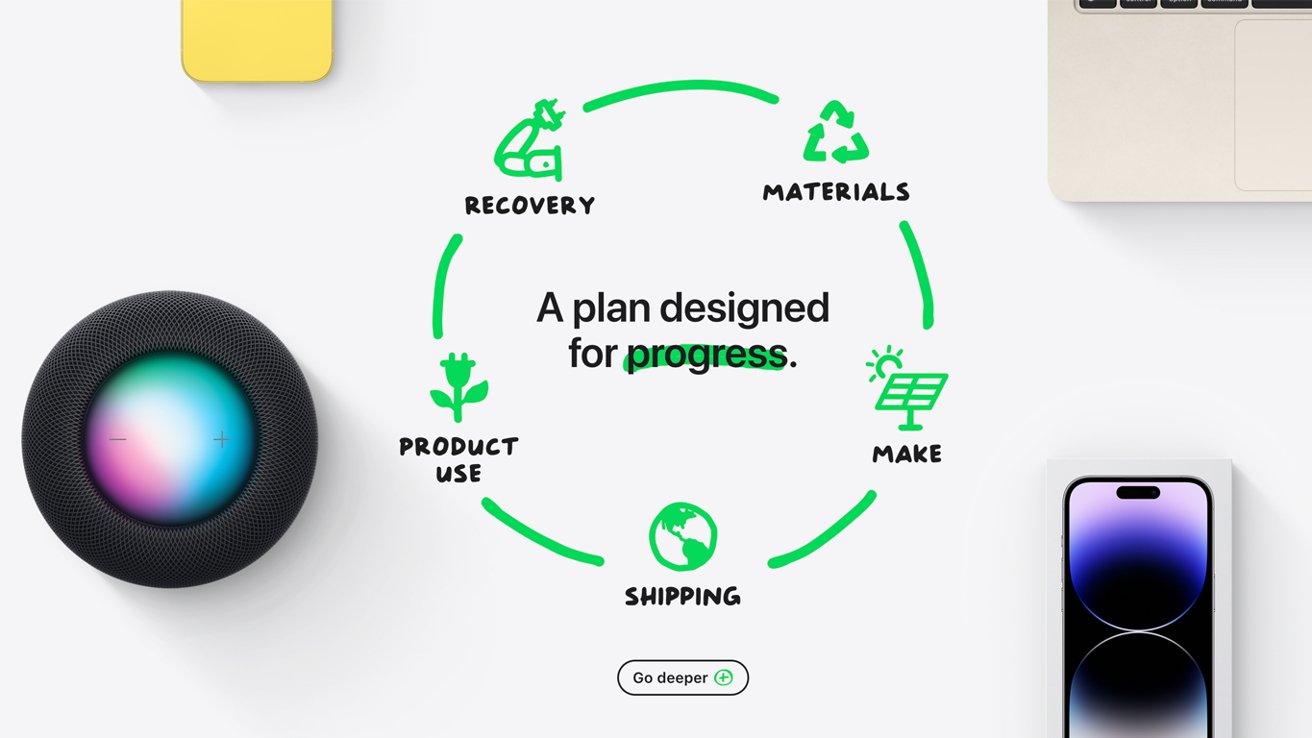

In 2020, Apple announced "Apple 2030;" a highly ambitious goal of becoming 100% carbon neutral by 2030. While Apple has already been carbon neutral on the global corporate level, the company wants to become carbon neutral across its entire business, manufacturing supply chain, and product life cycle.

Unfortunately, a yearly multi-device release cycle and now a rush to keep up in the artificial intelligence race are entirely counterproductive to those scales. While Apple has done an okay job at trying to minimize carbon production in its operations, there's no way to completely eliminate it.

In the past, most large corporations relied on carbon credits to offset the carbon they produced. Carbon credits are "generated" from projects that either avoid or remove carbon from the environment.

For instance, maybe a company adopts a patch of forest to protect it from deforestation. Maybe they invest in renewable energy startups. The point is, carbon credits are used to "offset" the carbon a company produces.

If a company produces 14.5 million metric tons of carbon in a year, that company can -- theoretically -- purchase 14.5 million carbon credits and become carbon neutral. But it's not that simple.

It's nearly impossible to figure out how much carbon a carbon credit project removes. This is why carbon credits are often panned as greenwashing: a strategy designed to signal to the public that the company is environmentally friendly.

A lot of big companies have shifted toward investing in eucalyptus farms in Brazil, hoping that the fast-growing tree could help tackle many environmental issues, including carbon emissions.

Science and technology journalist Gregory Barber took a trip to Brazil to check out these Apple tree farms. His story in the MIT Technology Review takes a critical look at this strategy.

It's a good, if not long, read I'd suggest checking it out if you're the kind of person who finds this sort of thing interesting.

The theory is that if you plant enough trees you can trap enough carbon dioxide and lock it inside the trees' lignin. Lignin is, essentially, the muscular-skeletal system of a plant, and it's most prevalent in woody trees -- like eucalyptus.

Planting eucalyptus forests in Brazil, a country hit hard by deforestation, seems like a logical solution. You'd just need to take large patches of land that used to be forest and replant a fast-growing forest.

Of course, it's not a perfect solution. Truthfully, it just cuts the middle man out of the carbon credit ecosystem. Environmentalists have long been critical of this solution.

Barber spoke to Giselda Durigan, an ecologist at the Environmental Research Institute of the State of Sao Paulo, who was highly critical of the idea. Like many others, Durigan worries that these farms are mostly a vanity project.

Image Credit: Apple

"They are using the carbon discourse as one more argument to say that business is great," Durigan said. "They are happy to be seen as the good guys."

The first glaring problem is that eucalyptus aren't native to Brazil, or even to South America. It's native to Australia.

Introducing non-native species always has significant drawbacks. Eucalypts are fast-growing, a feature that makes them good at trapping carbon dioxide.

However, fast-growing isn't necessarily better, either. Fast-growing plants tend to invade areas and choke out other species, though allegedly this isn't as big of a concern in Brazil.

But its fast-growing nature means the plant is necessarily water-hungry. Eucalyptus has been used as an effective strategy to control the spread of malaria because it's effective at draining swampy areas dry.

And there's also the argument that if you plant a fast-growing plant, be it eucalyptus or bamboo, you can harvest that, rather than native species, industrial uses. You can use bamboo to make paper, toilet paper, and textiles. Eucalyptus can be used to make paper, flooring, furniture -- pretty much the same as any other type of timber.

But that doesn't change the fact that eucalyptus is a singular plant, and monocultures are often far more detrimental than the problem they hope to solve. Ecosystems are complex, so the solution was never going to be simple.

I don't have an answer to how to fix the problem; truthfully, I'm not sure if there is one. It just becomes apparent what won't fix it.

Humans have a history of tampering with the environment to meet their own needs, and it often has less than desirable results. Just as Henry Ford learned that planting rubber trees in Brazil wasn't enough secure a source of rubber, Apple may find that planting eucalyptus in the same country can't save the world.

Read on AppleInsider

Comments

Yes, the whole carbon credit business is a racket. And I find it bizarre that Cupertino-headquartered Apple supports planting eucalyptus trees. For decades these trees have been considered by many Californians to be an invasive species. They were heavily planted in California by many cities (and some developers) who prioritized fast growing trees without thinking of the later consequences. (Redwoods and other conifers were also used this way.) Basically when a eucalyptus tree dies or is removed, it won't be replaced by a eucalyptus tree.

I can see some argument for planting them as a cash crop in a reforestation effort with planned harvesting but monocultures are generally a bad thing, I hope some other native species are also used for these carbon credit programs. Lol, maybe they can plant more coffee plants, there's a shortage of beans right now.

But we are still going to use electricity anyhow. I suppose this is one compromise, an interim solution to offset some of the damage until we come up with better methods. At least Apple is making an effort here at leading by example. There are many other companies and organizations that do far less.

I don't agree that all carbon credits are empty greenwashing, but you are right to say that reforestation is. And you are also right to say that the real solution to the problem is less emissions, end of story. But if you think that Brazil's carbon credits are junk, try ours (Australia's) on for size - a large number of our credits are based on 'avoided deforestation' - which is where we say, well, we were going to clear this particular parcel of land for farming, but instead, we will promise not to clear it, and have that count as an equivalent of reforestation credits. And to anyone who says, "how is that promise guaranteed?" or "were you really going to clear it?" ... yeah. Great questions. Another great question is why does the rest of the world allows us to do this?

I promise I’ll cut back… after this next cup…

Look nothing is perfect, but they are very deliberate in making products as energy efficient as possible, average laptop consumes 1/2 the power of a PC and that since 2020.

More and more products are build with recycled materials. All that believe this can be done overnight and without trial and error is delusional …

One quote shouldn’t be missed:

” Researchers are still grappling with how to calculate the climate impact of these steady, and fluctuating, carbon emissions. According to one study, global wood harvests could add between 3.5 to 4.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere per year in the first half of this century. That would be around a tenth of all human emissions.”

From that perspective, the article did not read controversial to me at all. As is often the case in these things, the article is more of an obituary for an ecosystem than actual criticism. Project Alpha is basically a 2nd or 3rd generation carbon credit project, and the changes being made look good to me. They are balancing ecologist's concerns with the need to mass grow trees. There is an industrialization of planting and maintaining trees. They are learning how to do this better and more efficiently. This type of project needs to be improved and repeatedly done world-wide.

The "savanna" or cerrado ecosystem that these ecologists are trying to preserve is a dead man walking. It will never return to the "glory days" during these people's youths. It's global warming, and we've bought into about 4 to 6 °F of warming since these ecologist's childhoods (1960s to 1970s), even if CO2 emissions dropped to zero now. That's enough to change the hydrological cycle worldwide. On top of this, commensurate with this, is the presence of humanity in every place on the planet, and it is penetrating into these places. Our very presence, even in a small scale, changes ecosystems where-ever we go.

So, this ecosystem will change. It's inevitable. Even if they manage to prevent humans from entering and settling the area, the ecosystem will change. It really is an anthropocene. Instead of ignoring what we are doing to the world, we are going to design it. Virtually everything that you get in a grocery store, everywhere you go, has been touch by humanity. Every single animal, plant, vegetable, fruit, food product, has been designed by humans to be the way it is. It will only become more so in the future.

It's great that Eucalyptus can be replenished faster. In that case, develop new land for this purpose and use existing Eucalyptus populations.

Eliminating certain flora and never see that species returned in that area is not a solution.