When to use an external microphone or recorder to make your podcasts

You can record your podcast on your iPhone, but what you might not be able to do so easily is make sure that the audio sounds good. Buying a broadcast-quality microphone or a separate audio recorder can bring your podcasting up a level, and there is some hardware that we like.

L-R: Roland R-07, Zoom iQ6, Sony ICD-UX533

If you're recording an audio or video podcast, you do already have all the equipment you need right there in your iPhone. The sound quality is good, the video is excellent, you're ready to make a podcast. Except that this good microphone is little use when there are two of you speaking. And the video may be brilliant but while you're filming with that, the iPhone's microphone is completely pointing away from you.

One solution is to hire a crew to record the podcast audio and video for you while you concentrate on the script and the presentation, but that's expensive.

There may well be times when that's your best option, but for most podcasts, you will be better off spending money on equipment instead. Maybe it'll take you time to learn how to get the most out of it, and maybe the equipment isn't exactly cheap, but it's something you'll buy once and use forever.

You need either a great microphone that you can plug into your iPhone, or you need a great microphone that comes built in to a separate audio recorder.

As good as the Zoom iQ6 is, its Lightning connector means it is only going to record audio to the side of what you're filming

Okay, it's too strong a word to say that you need this. Once you've used more than your built-in iPhone mic, though, you'll not want to go back. There are BBC Radio professionals who swear by broadcast-quality microphones that you plug into your iPhone's Lightning port.

We compared that with what's been a stalwart recorder for us, the old Sony ICD-UX533. That's still available used for around $120 but if we were buying it today, we'd get the updated ICD-UX560 which is $80.

Then we also tried that BBC Radio producers' choice, the Zoom iQ6 which plugs its stereo microphones into the Lightning port of your iPhone and costs $99.

And lastly, to give a baseline comparison, we went completely the other way. Instead of an iPhone with different mics and audio apps, we recorded on a Mac. We used macOS's free QuickTime Player and we recorded using a Blue Yeti microphone.

A Blue Yeti microphone in front of a Mac

Strictly speaking, the Roland R-07 is also aimed at musicians and comes with extra ports for connecting instruments or microphones to it, but to explore this for podcasting, we stuck to voice recording. With all of these devices switched on and recording simultaneously, we did a podcast.

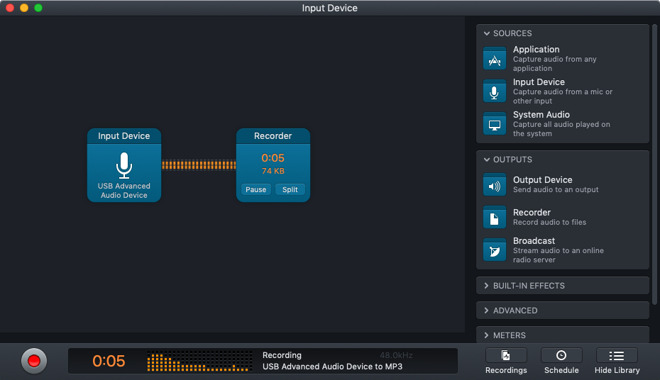

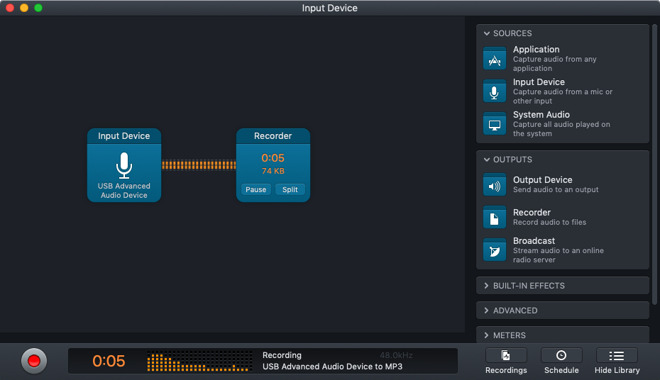

Then, too, if you're recording a podcast with someone else, you can use a Mac app such as Rogue Amoeba's Audio Hijack to simultaneously record both your microphone and the Skype, FaceTime Audio, Slack or Discord conversation.

This means you end up with multiple tracks and they all sound good. You can finish the recording and be sending the audio off to your editor immediately. Whether that's you or someone else, the editor may well have to do some work cleaning up the audio but otherwise this is a simple, fast workflow. You go from recording to having the files ready immediately.

Audio Hijack recording that Blue Yeti microphone directly into the Mac

You don't get that with any other option when you're recording on an iPhone. Even if you use the built-in microphone, you still have to record in an app such as Apple's Voice Memos, and then get that audio off the phone.

Subjectively, we liked the Roland and the Sony audio recorders better than we did the Zoom iQ6 audio quality. Plus that Zoom proved the hardest to set up. There's only a single Gain control on the device but it took very fine adjustments to get clear audio without picking up a lot of extra noise.

Waveforms of the same audio as recorded on the four different sources

We did get the clear audio, though, and none of this is going to work well if you hope to just plug it in and start recording. All of the devices benefit from you trying out their different options.

Plus the Zoom, while plugging into your iPhone's Lightning port, comes with a regular headphone jack. It's an expensive way to add back wired headphones to your iPhone, but for monitoring the recording as you experiment, it's good.

Each of the devices we used -- including the Blue Yeti -- have a headphone jack, and the audio quality was the same. What makes the difference in which will be best for you and your podcast comes down to physical form.

The Sony ICD-UX533, and its later versions, are the slimmest. It's powered by one AAA battery, and depending on the settings you choose, it will record for between 22 and 30 hours. Those recordings are kept on internal 4GB storage.

In comparison, the Roland R-07 uses two AA batteries and gets something in the order of 16 hours of recording. However, its recordings are stored on micro-SD cards, so you can have as much storage as you have cards. The one provided with ours was 8GB.

It's not as easy swapping out micro-SD cards as it could be. There's a protective flap but when trying to change cards, we still managed to make the provided spring out of the unit and go across the room.

Roland specifies that not all USB cables will work, though. You can't use one that's made just for charging, it has to be built for data transfer too. In practice, there's no way to tell if you've got the right cable until you try it. Yet once we got one that worked, we just kept it with the Roland R-07 that we always knew we could remove the audio.

The Sony ICD-UX533 has a more direct method for getting audio off. It's as if it has a flick-USB connector. You press up on a control and a full-size USB connector pops out of the unit.

Without question, that is by far the handiest and the fastest way to get audio off a recorder and onto your Mac -- so long as it fits. Even though it's slim, the Sony recorder is a lot thicker than a USB cable and this connector is literally just the connector. There's no cable run. So as handy as it is, you can find that you struggle to get the connector into that socket on the back of your Mac mini.

This all makes the Zoom good for when you're recording an audio source that's near you and your phone. Both the Sony and the Roland can be placed nearer your interviewee, or your musical instruments.

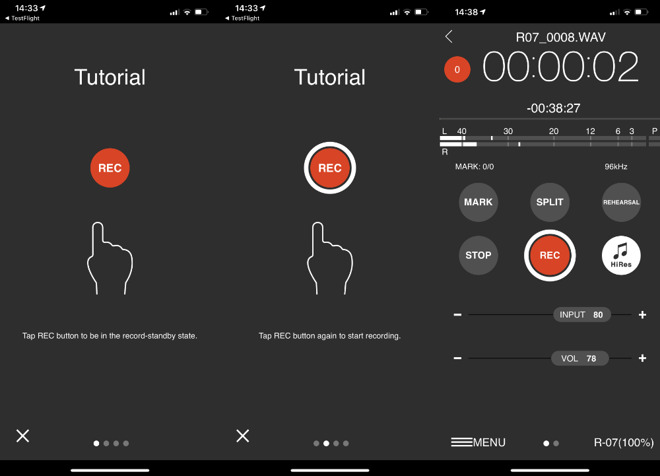

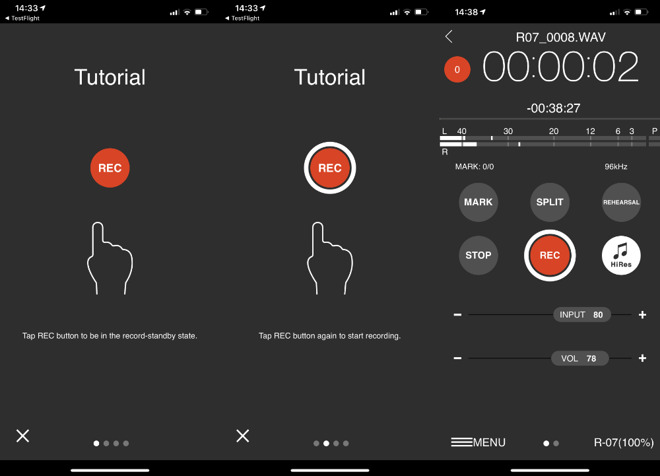

Roland's unit wins here, though, because it also comes with an app -- a remote control one. With that software installed, you can pair up to four R-07 recorders with your phone and then control all of them.

The Roland R-07 has a companion iOS app for remote control

It's a superb app. If you're used to recording, then you know the fear of not having started the recorder or of something going wrong. With this remote control Roland app, you can start the recording when you're ready and you can always see the status of that

So the next time we're in a BBC studio, you can bet we'll use the Zoom. Next time we're going to do an interview for print rather than podcast, we'll slip the Sony ICD-UX533 in our pockets the way we have for years.

And when we want to do a more substantial recording, such as broadcast quality for a podcast or the audio for a video, we'll use the Roland R-07.

Keep up with AppleInsider by downloading the AppleInsider app for iOS, and follow us on YouTube, Twitter @appleinsider and Facebook for live, late-breaking coverage. You can also check out our official Instagram account for exclusive photos.

L-R: Roland R-07, Zoom iQ6, Sony ICD-UX533

If you're recording an audio or video podcast, you do already have all the equipment you need right there in your iPhone. The sound quality is good, the video is excellent, you're ready to make a podcast. Except that this good microphone is little use when there are two of you speaking. And the video may be brilliant but while you're filming with that, the iPhone's microphone is completely pointing away from you.

One solution is to hire a crew to record the podcast audio and video for you while you concentrate on the script and the presentation, but that's expensive.

There may well be times when that's your best option, but for most podcasts, you will be better off spending money on equipment instead. Maybe it'll take you time to learn how to get the most out of it, and maybe the equipment isn't exactly cheap, but it's something you'll buy once and use forever.

You need either a great microphone that you can plug into your iPhone, or you need a great microphone that comes built in to a separate audio recorder.

As good as the Zoom iQ6 is, its Lightning connector means it is only going to record audio to the side of what you're filming

Okay, it's too strong a word to say that you need this. Once you've used more than your built-in iPhone mic, though, you'll not want to go back. There are BBC Radio professionals who swear by broadcast-quality microphones that you plug into your iPhone's Lightning port.

What we tested

The prompt for this piece was in part because of a recommendation by BBC Radio 4 producers in the UK. However, it was also prompted by the release of the Roland R-07 audio recorder which is being specifically marketed for podcasters. This is a handheld recorder with stereo microphones and the retail price is $230 but a typical street price is $196.We compared that with what's been a stalwart recorder for us, the old Sony ICD-UX533. That's still available used for around $120 but if we were buying it today, we'd get the updated ICD-UX560 which is $80.

Then we also tried that BBC Radio producers' choice, the Zoom iQ6 which plugs its stereo microphones into the Lightning port of your iPhone and costs $99.

And lastly, to give a baseline comparison, we went completely the other way. Instead of an iPhone with different mics and audio apps, we recorded on a Mac. We used macOS's free QuickTime Player and we recorded using a Blue Yeti microphone.

A Blue Yeti microphone in front of a Mac

Strictly speaking, the Roland R-07 is also aimed at musicians and comes with extra ports for connecting instruments or microphones to it, but to explore this for podcasting, we stuck to voice recording. With all of these devices switched on and recording simultaneously, we did a podcast.

The harsh truth

For utter convenience and speed, the Mac's QuickTime Player and a Blue Yeti microphone win out over everything. The audio quality is excellent if you record in ideal conditions, such as in a soundproof room or with little extraneous noise.Then, too, if you're recording a podcast with someone else, you can use a Mac app such as Rogue Amoeba's Audio Hijack to simultaneously record both your microphone and the Skype, FaceTime Audio, Slack or Discord conversation.

This means you end up with multiple tracks and they all sound good. You can finish the recording and be sending the audio off to your editor immediately. Whether that's you or someone else, the editor may well have to do some work cleaning up the audio but otherwise this is a simple, fast workflow. You go from recording to having the files ready immediately.

Audio Hijack recording that Blue Yeti microphone directly into the Mac

You don't get that with any other option when you're recording on an iPhone. Even if you use the built-in microphone, you still have to record in an app such as Apple's Voice Memos, and then get that audio off the phone.

The better truth

Take a look at our four simultaneous recordings being edited together. For the most part, you'd be pressed to see a difference. There are some but overall the quality of all our options was the same.Subjectively, we liked the Roland and the Sony audio recorders better than we did the Zoom iQ6 audio quality. Plus that Zoom proved the hardest to set up. There's only a single Gain control on the device but it took very fine adjustments to get clear audio without picking up a lot of extra noise.

Waveforms of the same audio as recorded on the four different sources

We did get the clear audio, though, and none of this is going to work well if you hope to just plug it in and start recording. All of the devices benefit from you trying out their different options.

Plus the Zoom, while plugging into your iPhone's Lightning port, comes with a regular headphone jack. It's an expensive way to add back wired headphones to your iPhone, but for monitoring the recording as you experiment, it's good.

Each of the devices we used -- including the Blue Yeti -- have a headphone jack, and the audio quality was the same. What makes the difference in which will be best for you and your podcast comes down to physical form.

Form follows function

The Zoom iQ6 is the smallest unit, coming with stereo microphones angled away from each other to give the maximum recording coverage. It's wide, however, and so much so that you can't rest an iPhone flat on a table when it's plugged in. You have to prop the phone up, but then because that encourages you to more carefully direct and position the microphone, you get better recordings.The Sony ICD-UX533, and its later versions, are the slimmest. It's powered by one AAA battery, and depending on the settings you choose, it will record for between 22 and 30 hours. Those recordings are kept on internal 4GB storage.

In comparison, the Roland R-07 uses two AA batteries and gets something in the order of 16 hours of recording. However, its recordings are stored on micro-SD cards, so you can have as much storage as you have cards. The one provided with ours was 8GB.

It's not as easy swapping out micro-SD cards as it could be. There's a protective flap but when trying to change cards, we still managed to make the provided spring out of the unit and go across the room.

Getting recordings

You can put Roland's micro-SD card into a reader and take the audio off that. You can also, though, plug one end of a USB cable into the unit and the other into your Mac. It appears as an external drive and you can just drag the audio off.Roland specifies that not all USB cables will work, though. You can't use one that's made just for charging, it has to be built for data transfer too. In practice, there's no way to tell if you've got the right cable until you try it. Yet once we got one that worked, we just kept it with the Roland R-07 that we always knew we could remove the audio.

The Sony ICD-UX533 has a more direct method for getting audio off. It's as if it has a flick-USB connector. You press up on a control and a full-size USB connector pops out of the unit.

Without question, that is by far the handiest and the fastest way to get audio off a recorder and onto your Mac -- so long as it fits. Even though it's slim, the Sony recorder is a lot thicker than a USB cable and this connector is literally just the connector. There's no cable run. So as handy as it is, you can find that you struggle to get the connector into that socket on the back of your Mac mini.

Extras and software

There's no need for any physical connection with the Zoom iQ6 as it's already connected to your iPhone and is storing audio in whatever app you use there. You can get iOS audio recording apps that are built for the Zoom but Apple's own Voice Memos is as good and is substantially easier to use.This all makes the Zoom good for when you're recording an audio source that's near you and your phone. Both the Sony and the Roland can be placed nearer your interviewee, or your musical instruments.

Roland's unit wins here, though, because it also comes with an app -- a remote control one. With that software installed, you can pair up to four R-07 recorders with your phone and then control all of them.

The Roland R-07 has a companion iOS app for remote control

It's a superb app. If you're used to recording, then you know the fear of not having started the recorder or of something going wrong. With this remote control Roland app, you can start the recording when you're ready and you can always see the status of that

Not a showdown

This isn't a case of taking several devices and saying one is the best. It's a case of saying that there are times when different solutions are right for you.So the next time we're in a BBC studio, you can bet we'll use the Zoom. Next time we're going to do an interview for print rather than podcast, we'll slip the Sony ICD-UX533 in our pockets the way we have for years.

And when we want to do a more substantial recording, such as broadcast quality for a podcast or the audio for a video, we'll use the Roland R-07.

Keep up with AppleInsider by downloading the AppleInsider app for iOS, and follow us on YouTube, Twitter @appleinsider and Facebook for live, late-breaking coverage. You can also check out our official Instagram account for exclusive photos.

Comments

There a few factors that cue a listener that a recording is an amateur project and not high-quality professional. Listeners may not be able to articulate what exactly they're hearing, but not being able to put a name to the problem doesn't prevent them from hearing it.

The most obvious of these factors is room reflections (followed closely by poor mic technique). A microphone picks up whatever sound is present, and doesn't differentiate between the sound you want it to record and what you wish it wouldn't. You don't realize just how reverberant a typical bedroom or living room is compared to an acoustically treated studio until you compare the same equipment on the same source in both. The difference is night and day.

Fortunately you don't have to spend a fortune to get a room sounding good enough for a podcast. Just hanging heavy blankets around the recording area will help a lot. If you have a bit of budget but don't want to spend too much or permanently alter the room, look into theatrical curtains. Any hard, flat surface is an enemy. Bookcases full of different sized books help reduce slap echoes and smooth out the room reverberation. Acoustically absorbent materials like blankets, cushions, stuffed furniture (and professional sound absorbing panels) all help reduce room reverberation. If you can leave some dead air space between the absorber and the hard wall, even better (in other words, hang the blankets six inches away from the wall instead of right against it).

Once you have a decent recording space, the next step is to work on mic placement and vocal technique. Once you have a handle on all that, THEN look into better equipment. You'll be amazed how much better your recordings will be with a couple simple improvements to the room and your technique.

Separately, I have a general question about microphones. People generally tout a nice desk top or boom mounted mic, yet if you watch TV the hosts all use lavaliere mics and they sound fine. What gives?

I have one that I keep with me for when I don't have my main recording rig to hand i.e. if I accidentally come across some interesting sounds outside work. They're great but very susceptible to wind noise, including if you move the phone quickly indoors. I highly recommend also getting a fluffy windshield e.g. the Rycote (link below). I find it almost unusable without one. Also you need to have your phone in Airplane mode or you get the cell tower interference on the recording. Even with these caveats it's a great little thing and I highly recommend it.

https://www.amazon.com/Rycote-Mini-Windjammer-Zoom-4n/dp/B00BMSX2GI/ref=sr_1_fkmrnull_2?keywords=zoom+h4n+mini+windjammer&qid=1555829046&s=gateway&sr=8-2-fkmrnull

Why not just use a conventional UHF wireless system? The output of the receiver can be fed into the phone the same way a microphone would.

To answer your question, Denon makes a Bluetooth receiver that would do what you describe. https://www.denonpro.com/index.php/products/view3/dn-200br

The AT2020 is a rare animal in that it manages to sound pretty good without costing very much. A decent-sounding lav will cost three times as much and still not sound anywhere near as good. They're used on TV for reasons of convenience, not sound quality. Anything not on camera, like voice-overs, is recorded in a vocal booth with a "conventional" mic on a boom. Lavs only sound good on TV because they use expensive, high-quality mics, EQ and noise reduction are usually applied, they're usually in an acoustically treated room/studio, and you can't hear them side-by-side with a conventional mic for comparison.

Controlling sibilance is a common problem, and easily solved with most professional recording software via a "de-ess" plug-in. I have no idea if such a thing exists for iOS. Is there a reason you need to use a phone as the recorder? Could you use a computer instead?

Apps to "clean-up" the sound in post can assist in equalization and level limiting, but if the original recording lacks a wideband frequency response or if the original recording is distorted, there's no effectively fixing that. But it is remarkable what people are able to achieve today on these tiny digital devices. I'm old enough to remember when we used crappy cassette decks where the tape ran at just 1 5/16 inches per second (in the studio, we recorded at 15 ips and many studios recorded music at 30ips, especially if they weren't using Dolby noise reduction) and so the frequency response was quite limited. If you didn't use an external mic, you picked up noise from the motor in the deck and even if you did, the frequency response of small mics was also extremely limited back then.

The difference you describe between then and now is the result of improvements in technology and manufacturing, NOT the size of the mic.

The size of the capsule, contrary to popular mythology, does NOT affect the frequency response of a microphone. The most accurate measurement mics in the world use a 1/4" diaphragm. Sales people (and many self-trained practitioners) will insist that a larger capsule increases low frequency response. Its not true. The benefit of a larger capsule is lower self noise. Even that assumes all else being equal, with the only difference between two mics being the size of the diaphragm. It's possible for a well-designed small capsule mic to have lower self noise than a cheap, poorly designed large capsule mic.

The myth probably originated from most small capsule mics being omnidirectional, meaning they don't exhibit the bass-boosting proximity effect you get with the cardioid pickup pattern favoured by most low-to-mid-priced large capsule mics.

I perform spoken word in coffee shop venues. The video's adequate but unless my photographer's in the front row (seldom) the sound is focused more on the people around the phone than on me at the stage. So I've been looking for a lavalier BT mic that would feed directly into the phone. (I know me and know I won't take the time to mate up separate soundtracks with the video after the fact. And bluetooth quality should be good enough. Certainly a big step up from what I get now.)

I don't understand the perceived benefit of Bluetooth over conventional, existing wireless microphone systems. You can go into any music store and buy a Sennheiser G series lav mic with body-pack transmitter and compact receiver for around $500. There are even cheaper systems, but I haven't used them myself so I can't speak to their efficacy. In my experience the risk of drop-outs and fizzy noises is much higher and range is much lower with anything under five hundred bucks.

Do you even really need wireless? Could you run a cable from your position on stage to the camera position? That would be less expensive.

Thanks for your many posts by the way; clearly, you know what you're doing at the mixing board!

If you're working at a professional level I recommend making the investment in Pro Tools. While there's no question it's both expensive and overkill for VO work, the quality of the processing is much better than the stock Apple AU plug-ins so the finished product sounds a lot better. It's also by far the best audio editing platform.

I’d also suggest you look at the Bluetooth mic called the MikMe - I’ve recorded programmes for BBC World Service Radio using just the MikMe and my phone. I’ve edited whole programmes on the Ferrite multi track audio editor app too - think Adobe Audition on a phone. If you want to hear the quality of the mic you could hear it being used on a podcast series I made https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p06gqq99 which was recorded in the UK and Egypt and edited on an iPhone X using Ferrite.

And for those of us without all those dollars or pounds: I’d suggest two things - the internal mic of the iPhone with a cheap 50mm windshield from Amazon or - for single contributor ‘rants’ - the bundled earbuds and their online mic. Both of these come into their own if you’re recording outside. The background atmos does away with the mic limitations and is perfectly ‘broadcast quality’. At a guess I’d say I’ve used the internal iPhone mic for 80% of the live and recorded pieces I’ve done over the last ten years (at a conservative guess that would equate to about 5000 pieces of radio). If you want to find out more about the mobile journalism work I and my colleagues and friends are working on you could do worse than follow @marcsettle and @documentally. I’m @nickgarnettbbc on Twitter. If anyone wants to get in touch with me or the others, or needs any help getting the best out of their phones, we’ll always do our best to help.

Yeah, for sure, this ^^^. But, as above, picking the right mic (not necessarily the expensive ones) can also make a big difference.

The Yeti is a good mic in the right environment, but I'm not sure why they are so often recommended to podcasters getting started, as it kind of sets them up for trouble if they can't achieve the environment.

re: app - Give Auphonic a try: https://auphonic.com

re: TV Hosts - Yeah, with video, they often want to keep a mic out of the picture, so they go with other types of mics. But, those typically require more techie work or a better environment, as far as I know (I don't have much experience with shotgun mic). If you're using it for video work, that might just be a tradeoff you'll want to make.

In addition to what Lorin said (in response to Neutrino) I've got the ATR2500, which I think is a somewhat similar beast. Just remember that these are both condenser mics, so the environment is crucial. The pop filter is good, but also remember that you're talking more 'across' the mic, not into it (just in case you're not aware). You don't have to be right on top of them like you do a dynamic mic, either, though if you can be closer/consistent, it makes eliminating noise easier.

The video application is key, as that will more determine the mic type than it would for a podcaster.

I'd still recommend a dynamic mic to most podcasters. The reason I picked a condenser, is that I don't want to have to keep my head in such a precise placement compared to the mic and I'm willing to deal with the environment stuff. That said, I might also pick up an ATR2100 so I have the option for when the environment is noisier.

Obviously content trumps audio quality, and if the show is good enough, people will overlook imperfect sound. Bad sound is still distracting though, and it gives listeners a reason to tune out. When it's so easy and inexpensive to do better, why set the bar at it's lowest rung? In the OB van in the middle of a hurricane, sure, use whatever you have on hand. If you have or can easily access better, why would you deliberately compromise the listening experience?

Different mics have different pickup patterns. Some are omnidirectional, designed to pick up sound from every direction more-or-less equally. Others are more directional -- more sensitive to sound in front of the mic than to sound beside or behind it. The more directional the pickup pattern, the less extraneous noise is captured. It ain't a free lunch though, it comes with gotchas.

One is that you obviously have to control your own movements. With a tight pickup pattern, the sound will change as you move around in front of the mic. Another is that very directional mics also tend to be more sensitive to plosives (like P-pops). Third, they exaggerate lower frequencies, so while it might seem cool to "fatten up" your voice by getting close to a directional mic, you can very easily go too far and overwhelm the listener with excessive bottom end (which, if you're using typical, affordable speakers or headphone for monitoring, you won't even be aware of because you don't get very good low frequency response without spending long coin). Fourth, they don't reject all frequencies evenly so it's only one part of a more complete noise-abatement strategy.

Bottom line 1: Mic choice depends as much on your environment, style, and technique as it does any objective measure. That's why pro studios have a variety of options and choose the one best suited to the task at hand. You should try several in your own setting and keep the one that works best for you in your particular space.

Bottom line 2: How well a mic performs has as much to do with the skills of the person in front of it as anything inside it.

There is so much hardware to choose from and it's constantly evolving. These are exciting times for audio production.

As I record editorial, experimental and artistic projects I can get totally hung up on the hardware and occasionally forget the value gleaned from using a simple set up.

I might use the Sound Devices MixPre-6, the Zoom H5, the Sony PCM D100 or the Zoom H1n. Some of the mics I use with these vary from Lav mics, shotgun mics, the Rode NT4, a hydrophone or binaural headsets. I take the microSD cards out of these devices and via a lightning card reader edit mainly on the iPhone using VRP7 for single track or Ferrite for multi track.

But my passion lies with recording to the phone. I've recorded more than 2000 podcasts and social audio clips just using a mic shield (as Nick Garnett recommended above).

There is something to be said for the intimacy of immediate capture and share. Too many try to sound like the radio and podcasting can be so much more. If I have the gear with me I'll might use the Sennheiser Hand Mic or their Ambeo Smart Headset. Recording in stereo delivers more accessible, visual audio and binaural does even more. Here is an experiment recorded in a canal tunnel last week.

I also have the Sennheiser XSWD and the Rode Wireless GO as simple 2.4g wireless solutions that are worth looking at.

Just to throw a spanner in the works I'm currently compiling a mixtape (a TDK90) with field recordings captured with many of the above devices and mics. These recordings have never been online and in some ways I hope they never do. It's a long process and I might only manage one every two months. It's a great way of learning how all this gear performs in different environments. If you are interested I call this Audiocaching and invite anyone passionate about audio to have a play.

All work and no play can make for some stale and ordinary sounding audio. So play, experiment and most of all have fun!