TSMC's US factory shows the limits of reshoring, tariffs, and corporate welfare

A new examination of Apple partner TSMC's Arizona facility shines a spotlight on how the U.S. bet on domestic chipmaking is colliding with labor shortages, cost overruns, and global dependencies.

TSMC's U.S. expansion efforts face global scrutiny

Just outside Phoenix, a sleek, high-security facility is taking shape. Known as Fab 21, the site is operated by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and will soon be one of the most advanced chipmaking facilities in the world.

The microscopic transistors produced here will power Apple devices, artificial intelligence systems and critical infrastructure, representing a significant shift of advanced technology manufacturing to American soil.

TSMC currently makes about 90% of the world's most advanced semiconductors, nearly all of them in Taiwan. That long-standing reliance is now being reexamined amid global supply disruptions and rising tensions in the Asia-Pacific.

Engineering precision at tiny levels

Inside Fab 21 as reported by the BBC, workers operate in one of the cleanest environments on Earth. Clad in full-body protective gear, they move through sealed clean rooms where even a single dust particle could ruin an entire silicon wafer.

Each wafer takes over 3,000 precise steps to complete and can contain hundreds of chips, each with tens of billions of transistors. One of the first wafers produced at the site featured 4-nanometer chips holding up to 14 trillion transistors per chip, according to TSMC.

These chips are fabricated using extreme ultraviolet light, a process involving plasma generated from molten tin and bounced through precision optics. The machinery required is built by ASML, a Dutch company that supplies the only lithography systems capable of producing these advanced nodes.

TSMC replicated much of its Taiwan production environment in Arizona, but the complexity of the process means the US still relies heavily on foreign equipment, materials and expertise.

Controversies and growing pains

The Arizona plant hasn't progressed without friction. Construction delays and cost overruns pushed back initial production to 2025, with a second 2-nanometer fab now targeted for 2028.

In 2023, TSMC flew in hundreds of engineers from Taiwan to keep the timeline on track. US labor unions criticized the move, arguing that the company had not done enough to train local workers.

Taiwanese workers brought to the US have reported challenges adjusting to local conditions, from language barriers to regulatory complexity. Some describe long hours and pressure to meet aggressive targets under unfamiliar rules.

Behind the scenes, executives have voiced frustration with US permitting processes, labor availability and cultural differences in workplace norms. Building chips at scale in America has proven far more expensive than in Taiwan, despite federal subsidies.

TSMC's Arizona factory. Image credit: BBC

Officially, Taiwan's government supports TSMC's global expansion. Privately, there is concern. Taiwan's dominance in semiconductors, sometimes called the "Silicon Shield," is seen as critical leverage in deterring Chinese aggression.

Moving high-end production overseas may reduce that leverage and undermine the island's geopolitical relevance.

Some in Taipei have warned against letting the US or other allies "hollow out" Taiwan's tech advantage. Others view diversification as necessary insurance against supply chain shocks or military threats.

Trade pressure and federal subsidies shaped the move

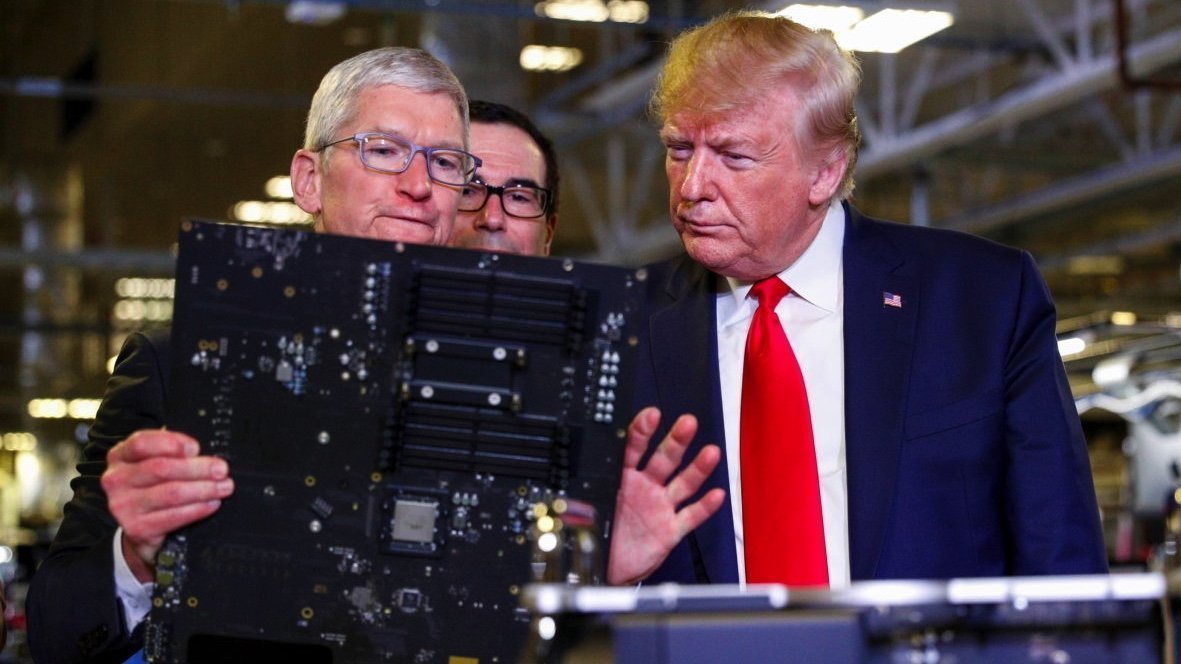

President Donald Trump frequently cited TSMC's US investment as proof that his tariff threats worked. His administration pushes to reduce US dependence on Asian manufacturing, using trade pressure to encourage reshoring.

Former President Joe Biden focused on subsidies and long-term industrial planning. The CHIPS and Science Act, signed into law in 2022, offers tens of billions in funding and tax incentives.

TSMC's Arizona project is the largest foreign beneficiary, with $40 billion committed across two construction phases. Phase one is expected to produce chips in 2025.

Despite the political divide, both administrations have treated semiconductor independence as a bipartisan priority. TSMC's presence in Arizona is the centerpiece of that effort.

Semiconductors are no longer just a tech industry issue. They are now seen as the foundation of economic security, artificial intelligence leadership and national defense.

Trump pushes to reduce US dependence on Asian manufacturing

The Arizona fab is a central piece of the US strategy to localize chip production, reduce dependence on Taiwan and stay ahead of China in advanced computing.

Bringing TSMC to the US gives American firms closer access to their most critical components. It also gives Washington a foothold in reshaping global supply chains around trusted partners.

But the project's significance runs deeper than corporate logistics.

Strategic chips for the AI era

The Arizona facility is producing chips not only for smartphones and laptops but also for artificial intelligence, cloud computing and defense applications. Companies like Apple and Nvidia have confirmed plans to use chips from Fab 21 in upcoming US-bound products.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations have moved to block China's access to these technologies. The US has restricted exports of ASML lithography tools and banned companies like Huawei from acquiring high-end chips.

Still, China is racing to catch up. US restrictions have pushed Beijing to go full speed ahead. That's part of why leaders in both parties continue to push for domestic capacity.

Looking ahead to a fragmented future

TSMC's Fab 21 is part of a broader reshaping of the global semiconductor map. Intel is building new fabs nearby. Samsung is expanding in Texas. Arizona, already a hub for aerospace and defense, is becoming a critical node in America's plan to regain leadership in chip production.

But global interdependence will not disappear overnight. Key components still come from Japan, Germany and the Netherlands. Engineers from Taiwan continue to train the US workforce. Even the clean room garments are often imported.

As geopolitical competition escalates, the US faces a delicate balancing act. It must rebuild strategic capacity while staying connected to a global innovation network. The Arizona fab may not make the US self-sufficient, but it's a foundational step toward greater resilience.

Read on AppleInsider

Comments

Taiwan's chip dominance could be one reason China is hell bent on taking-over Taiwan. In this case the "silicon shield" works against them making them more desirable.

I don’t want to say that the most advanced chips cannot be made by TSMC in the US, but I can confidently say that it is naive in the extreme to suggest that it can be done quickly or easily here. Work culture in Taiwan is much different than it is in the US . Work-life balance does not exist the way we think of it here. The fabs in Taiwan have bookstores and flower stores, among others, right off the cafeteria. Why? So you never have to leave the plant. Is it your son’s birthday? Get a present for him at work before you get home at 10 PM.

I don't see this notion of owning this supply chain as viable anymore. So, the argument is moot.

30 years ago, the economics were such that it was possible. Development costs for fabs and customer bases were sufficiently low such that it could be done. Multiple micron-level fabs existed, that served that needs of a mainframe market or other small niche. Intel was ahead with leading edge fabs, but small companies could follow 6 to 12 months behind them with a near equivalent fab. AMD had its own fabs. Didn't Texas Instruments have its own fabs? TI! Before they gave up. IBM amazingly held on for a long while just serving their mainframe market.

Today, you need to sell into the entire population of the Earth to support the development of a leading edge, Angstrom level fab. It's Highlander rules, where there can only be one. It costs so much to develop a leading edge fab now, you need to have billions of chips shipped from your fab to make it worthwhile. To do that, you need to play a game of geo-politics, carving a path such that the chips coming out of the fab can be used everywhere in every nation.

If you don't do that, you will not get enough revenue to pay for the development of the fab. So, the notion that one nation can own the supply chain while serving the enter world is a fantasy. It's not even a fantasy. It's like saying gravity is optional or energy isn't conserved. The economics aren't going to work out.

Taiwan moves to tighten control over TSMC's advanced chip exports and overseas investments

Intel, IBM, Xerox, Motorola Schaumburg, Illinois, and US Steel failed due to management changes, the inability to recognize the importance of long-term product iteration and the need for ongoing research and development.

One other problem in America is the blame game, where production workers are blamed despite management’s bad decisions, which is another on going long term issue.

In America, MBAs, accountants, financial/bankers, and lawyers often end up running companies, especially in specialized fields like technology, pharmaceuticals, and high-end manufacturing. However, these elements should not be allowed to make strategic decisions or to run such companies, support yes run the company. Hell no….

Another big element is the time it’s gonna take to turn things around and no one in America wants to hear it but it’s probably overall two decades or more which is going to be a big problem in America because that’s stretched over five administrations oh boy……

Yes, the incentive structures of public companies can lead to some bad outcomes for companies. People have been aware of it for a very long time. Very successful enterprises can be ruined by just a few people, like Boeing or Intel. I don't think you can fix it as assholes are an inherent part of humanity. Some companies will have a spiral of bad decisions they can't recover no matter the structures erected to prevent it. There's probably government incentives to make businesses easier to capitalize, easier to build up to replace failed companies though.

Then, hard to believe a lot of these incumbent companies can maintain. Like Japanese car companies have essentially ceded, voluntarily, the car market to Korean and Chinese car companies, and whoever else up and coming. They won't be able to catch up. Those decisions are ingrained in some incumbents and it takes special leadership to effectively burn the ships and move forward. There needs to be incentives to make it easier for new businesses to pop up. And this is assuming the gov't knows what to do, and a lot don't.

When Gelsinger came in, he knew what needed to be done, which was to turn Intel into a merchant chip foundry as fast possible, in order to capture more and more of the chip market. Ten years late, but if they want to be leading edge, it needs to be done. They likely have to give some big discounts for years. You can't overcome 40 years of Intel's modus operandi of Intel and x86 in 3 years. Who knows if Intel's new management will push it through. Gelsinger needed to clean house at every management position to move fast on it. Who knows now.

Intel was an ARM licensee in the early aughts, making good StrongARM SoCs for PDAs. They cancelled that when they wanted Intel to be x86 all the time, everywhere. Obviously they said no to making iPhone ARM chips. The whole thing about selling chips for $30 per chip was anathema to them, and is likely still frowned upon. Then of course, the 10nm fab was a FUBAR of all FUBARs. Intel even knew GPU compute was going to be a future transition, but couldn't bring out a good GPU for about a decade? Maybe not yet even?

The pipeline of engineers and the education system for chip manufacturing is currently fine, imo. But yes, half the USA is quite anti-STEM, and the current gov't is virulently anti-STEM. So, it may not be fine soon. Very discouraging.