Massachusetts judge granted warrant to unlock suspects iPhone with Touch ID

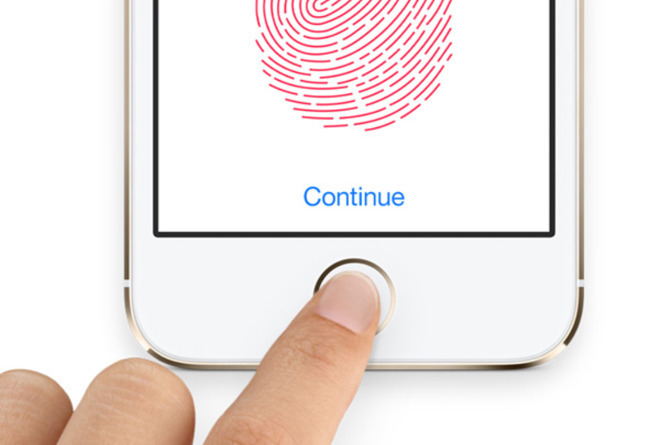

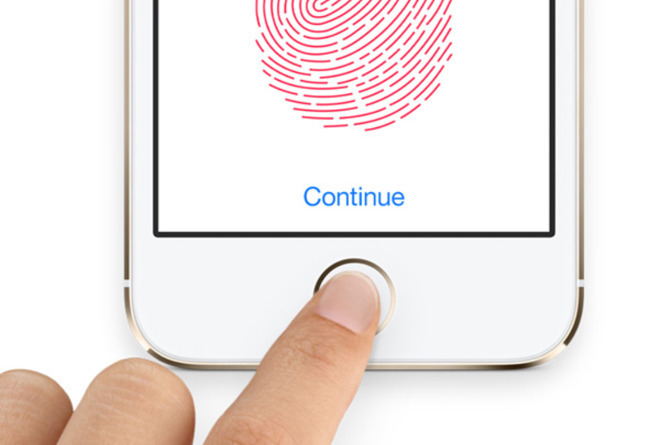

Law enforcement can compel a suspect to unlock their iPhone using Touch ID under a warrant, a Massachusetts federal judge ruled in April, muddying the waters in the ongoing battle in courts over whether the contents of a mobile device secured with biometrics are protected by the Fifth Amendment, or not.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) requested a search warrant that allowed agents to press a suspect's fingers against iPhones found at his apartment in Cambridge, using the digits to unlock the devices via Touch ID. The suspect, Robert Brito-Pina, was thought to have performed gun trafficking, and due to being a convict, was barred from owning any guns at all.

The warrant was issued on April 18 and expired on May 2, but it is unclear if the ATF managed to make use of the warrant during that time, reports Sophos. The warrant included arguments over how there was a limited window available before the iPhones would require a passcode to unlock it, something which likely helped the rapid granting of the warrant.

The iPhone was likely to contain evidence of Brito-Pina's alleged activities, with evidence that led to the suspect largely consisted of data from other smartphones and warrants served to Google. Text messages, locations for drop-offs in Waze, and photographs of illegal guns were discovered, along with communications about the sales and purchases of firearms.

The issued warrant is the latest in a number of decisions by judges as to whether or not law enforcement officials should be allowed to take advantage of biometric security and the availability of a suspect to access data on a mobile device. While passcoded devices are usually enough to protect suspects from having their smartphones searched by the letter of the law, biometric security is considered fair game for abuse.

A January court filing in California revealed another judge denied the use of a warrant to perform a biometric security unlock, with the request denied for running "afoul of the Fourth and Fifth Amendments." The judge declared the warrant was too "overbroad" in targeting any devices at a crime scene owned by anyone, rather than specific devices owned by the suspect as in the latest case.

For the January warrant attempt, it was reasoned that, while a user can state a passcode as a "testimonial communication," biometrics cannot be used in the same way as they can be acquired via unwilling means, such as forcing a suspect to touch the Home button on an iPhone, or holding a Face ID-equipped device to the suspect's face for a moment.

It was deemed that, if a person could not be compelled to provide the passcode, the same should apply for a finger, thumb, iris, face, or other biometric feature. "A biometric feature is analogous to the 20 nonverbal, physiological responses elicited during a polygraph test, which are used to determine guilt or innocence, and are considered testimonial," wrote Judge Kanis Westmore in January.

As the April warrant was limited in scope, and specific to the suspect's fingers and the suspect's iPhone, and very specifically not other people in the vicinity or devices that weren't iPhones in regards to unlocking. It is also not a green light for all law enforcement officials to use biometric security immediately upon device seizure, as warrants will continue to be required in such cases.

These are far from the only times law enforcement have attempted to use biometric security to gain access to mobile devices.

In 2016, one woman was made to use her fingerprint to unlock an iPhone confiscated from a property owned by an Armenian Power gang member, at the time in prison for unrelated charges. Police have also used fingers of corpses to attempt to unlock iPhones, albeit with limited success.

The FBI ordered the unlocking of an iPhone X via Face ID in August 2018, as part of a child abuse investigation in Columbus. The introduction of Face ID has also led to a forensic firm warning police to avoid looking at the screen of an iPhone X or similarly-equipped device, to avoid accidentally attempting an unlock that would automatically fail.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) requested a search warrant that allowed agents to press a suspect's fingers against iPhones found at his apartment in Cambridge, using the digits to unlock the devices via Touch ID. The suspect, Robert Brito-Pina, was thought to have performed gun trafficking, and due to being a convict, was barred from owning any guns at all.

The warrant was issued on April 18 and expired on May 2, but it is unclear if the ATF managed to make use of the warrant during that time, reports Sophos. The warrant included arguments over how there was a limited window available before the iPhones would require a passcode to unlock it, something which likely helped the rapid granting of the warrant.

The iPhone was likely to contain evidence of Brito-Pina's alleged activities, with evidence that led to the suspect largely consisted of data from other smartphones and warrants served to Google. Text messages, locations for drop-offs in Waze, and photographs of illegal guns were discovered, along with communications about the sales and purchases of firearms.

The issued warrant is the latest in a number of decisions by judges as to whether or not law enforcement officials should be allowed to take advantage of biometric security and the availability of a suspect to access data on a mobile device. While passcoded devices are usually enough to protect suspects from having their smartphones searched by the letter of the law, biometric security is considered fair game for abuse.

A January court filing in California revealed another judge denied the use of a warrant to perform a biometric security unlock, with the request denied for running "afoul of the Fourth and Fifth Amendments." The judge declared the warrant was too "overbroad" in targeting any devices at a crime scene owned by anyone, rather than specific devices owned by the suspect as in the latest case.

For the January warrant attempt, it was reasoned that, while a user can state a passcode as a "testimonial communication," biometrics cannot be used in the same way as they can be acquired via unwilling means, such as forcing a suspect to touch the Home button on an iPhone, or holding a Face ID-equipped device to the suspect's face for a moment.

It was deemed that, if a person could not be compelled to provide the passcode, the same should apply for a finger, thumb, iris, face, or other biometric feature. "A biometric feature is analogous to the 20 nonverbal, physiological responses elicited during a polygraph test, which are used to determine guilt or innocence, and are considered testimonial," wrote Judge Kanis Westmore in January.

As the April warrant was limited in scope, and specific to the suspect's fingers and the suspect's iPhone, and very specifically not other people in the vicinity or devices that weren't iPhones in regards to unlocking. It is also not a green light for all law enforcement officials to use biometric security immediately upon device seizure, as warrants will continue to be required in such cases.

These are far from the only times law enforcement have attempted to use biometric security to gain access to mobile devices.

In 2016, one woman was made to use her fingerprint to unlock an iPhone confiscated from a property owned by an Armenian Power gang member, at the time in prison for unrelated charges. Police have also used fingers of corpses to attempt to unlock iPhones, albeit with limited success.

The FBI ordered the unlocking of an iPhone X via Face ID in August 2018, as part of a child abuse investigation in Columbus. The introduction of Face ID has also led to a forensic firm warning police to avoid looking at the screen of an iPhone X or similarly-equipped device, to avoid accidentally attempting an unlock that would automatically fail.

Search Warrant 1 19 Mj 05101 JGD by Mike Wuerthele on Scribd

Comments

On iPhone 5s to iPhones 7:

On iPhones 8 and iPhone X:

This kind of approach to law, however well meaning the supporters may be, is what is eroding our country—the arrogance that we know better than our founders while we’re standing on the success they built... not realising that things are different now only because we’ve been slowly abandoning what they built in the name of ‘progress’.

So what if you have "sensitive non-criminal business or personal information” in a file cabinet along with your incriminating documents. With a warrant the police can open your file cabinet and search it without your permission. If you have it locked they can drill the lock without your permission. Your phone is no different than your file cabinet. These straw man 5th Amendment scenarios pop up every time a locked phone is involved.

So you are in the business of advising criminals how to avoid a warrant?

Edit: this one too: http://www.fox13news.com/news/local-news/judge-jails-man-for-failing-to-unlock-phones

But this case is no surprise, with a warrant the police have wider discretion. As long as the warrant is specific.