How Apple A-series chips stack up against Intel Macs

Apple Macs are moving away from Intel and to Apple Silicon. To understand what that means for Mac performance, it's helpful to look back at past A-series chips and compare them to Intel CPUs.

Apple Macs have long used Intel chipsets, but that's due to change within the next few years.

Since the very first iPhone, Apple has been using ARM-based processors in its mobile devices. The company launched its first true A-series chip with the iPhone 4, which came equipped with the Apple A4 chip. Since then, Apple's proprietary chips have been breaking ground and stretching the limits of what is possible from ARM-derived processors in a mobile package.

Now that we know future Mac devices are going to sport Apple Silicon too, it's helpful to look back at how recent Apple A-series chips compare performance-wise to Macs with Intel processors in them. Here's how the A10 through the A12Z stacks up against similarly performing Intel chips.

Credit: Apple

The A10 Fusion chipset was first released on the iPhone 7 and iPhone 7 Plus in September 2016. Despite its age, the A10 Fusion can still keep up with many current tasks thanks to its power.

Per Geekbench 5, the 2.3GHz A10 Fusion clocks in with a single-core of 740 and a multi-core score of 1322.

With those scores, it means the A10 Fusion chipsets are roughly similar to the early 2016 12-inch MacBook, which Apple has since discontinued.

The 12-inch MacBook equipped with a 1.3GHz Intel Core m7 processor clocked in with a single-core score of 652 and a multi-core score of 1405. It retailed for $1,299 at the time of its release.

Credit: Apple

After the release of the A10 Fusion, Apple adapted the chip for its tablet lineup with the A10X Fusion chip. Throughout its life, it powered the 6th-generation and 10.2-inch iPad, the 10.5-inch iPad Pro, and the 2nd-generation 12.9-inch iPad Pro.

The device benchmarks pretty similarly to the A10 Fusion, though it comes in slightly higher. On an iPad, it clocks in with a single-core score of 755 and a multi-core score of 1403. It's quite a bit faster on the aforementioned iPad Pros, with single-core scores of 831 and multi-core scores of 2265. The A10X Fusion could be had for as low as $649 on an iPad Pro.

With those scores, the A10X Fusion is in the same ballpark as a 13-inch MacBook Pro model from 2017. The specific variant we're comparing is the mid-range configuration with an Intel Core i5 processor, which retailed for $1,499.

The aforementioned 13-inch MacBook Pro clocks in with a single-core Geekbench 5 score of 850 and a multi-core score of 1972, meaning it's actually slightly slower in multi-core performance despite being more expensive than the iPad Pro.

Credit: Apple

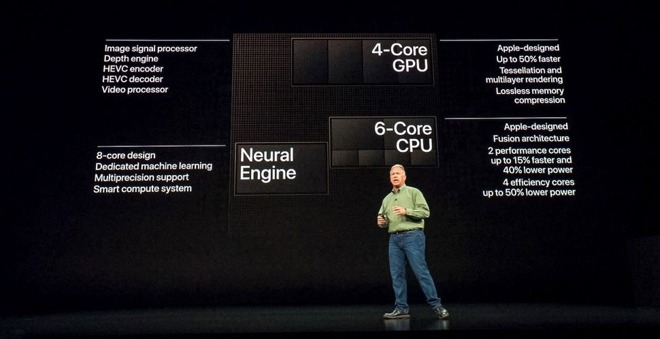

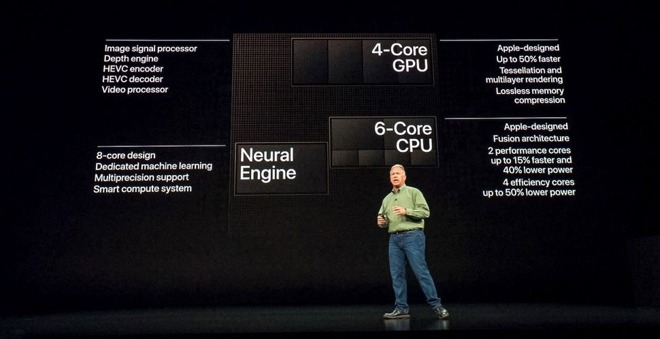

The A11 Bionic chip was introduced on the iPhone 8, iPhone 8 Plus and iPhone X in 2017. A dual-core processor, the A11 Bionic was also the first A-series chip to sport an Apple "Neural Engine" for A.I. and machine learning tasks.

On an iPhone X, the A11 Bionic came in with a 917 single-core and 2350 multi-core score in Geekbench 5 benchmark testing. While that device retailed for $999, the A11 Bionic could be found for cheaper in the iPhone 8 series.

The entry-level 2020 MacBook Air, equipped with an Intel Core i3-1000NG4, benchmarks similarly. It's a low-power 1.1GHz dual-core processor with Turbo Boost up to 3.2GHz.

The early 2020 MacBook Air (base model) equipped with the chipset has an average single-core score of 1076 and a multi-core score of 2842. The computer it comes in retails for $999.

Credit: Apple

The A12 Bionic, which first appeared on the iPhone XS, iPhone XS Max and iPhone XR, was Apple's first to be made with a 7nm chip process. (It also ended up in a non-X form in the 2019 iPad Air 3 and iPad mini.) The A12 could be had for $750 in an iPhone, or $399 in an iPad.

In an iPhone XS, the 2.5GHz A12 Bionic scored a 1106 and a 2687 in multi-core Geekbench 5 benchmark testing. In the latest iPad Air, benchmarks came in slightly higher with a single-core score of 1112 and a multi-core score of 2869.

That puts the A12 Bionic on roughly the same footing at the 2017 21.5-inch iMac equipped with a 3GHz Intel Core i5-7400 processor. That device started at $1,099.

In an iMac with 8GB of RAM, the Intel Core i5 scored a 1005 in single-core Geekbench 5 testing and a 3208 in multi-core benchmarking.

Credit: Apple

The A13 Bionic is currently Apple's latest iPhone chip, and it's installed in the iPhone 11, iPhone 11 Pro, iPhone 11 Pro Max and iPhone SE devices.

It's a 2.66 GHz, six-core processor. Per Geekbench 5 benchmarks, the A13 Bionic averages a single-core score of 1325 and a multi-core score of 3382. While the higher-tier iPhones pack it, you can get the A13 Bionic as cheap as $399 in Apple's 2020 iPhone SE.

If you want similar performance in a Mac, you'll probably want to take a look at the 13-inch MacBook Pro with an 8th-generation Intel Core i5-8257U processor. That MacBook processor is a 1.4GHz quad-core chip with Turbo Boost up to 3.9GHz, per Apple's specifications.

On Geekbench 5, it comes in lower than the iPhone in single-core scores but slightly higher in multi-core with 1012 and 3676, respectively. You can get that chip in an entry-level MacBook Pro for $1,299.

Credit: Apple

There are two generations of iPad-specific A12 chips that Apple has released in the past two years: the A12X, which was installed in the 2018 iPad Pro models, and the A12Z, which powers the 2020 iPad Pro models, as well as the Apple Developer Transition Kit.

Both chips benchmark similarly on Geekbench 5, mostly due to the fact that they are essentially the same piece of silicon with slight modifications (such as an extra GPU core).

The A12X and A12Z Bionic both benchmark around 1115 in single-core testing, but they clock in as the fastest iOS-based devices in multi-core benchmarks with a high score of 4626. On an Apple Developer Transition Kit running Geekbench 5 natively, the scores are roughly similar with single-core scores around 1005 and multi-core scores around 4555. The A12Z retails for $799 in an 11-inch iPad Pro.

If you want similar single- and multi-core performance in an Intel-based chip, the way to get it is the mid-range 16-inch MacBook Pro with Intel Core i7 processor. It retails for $2,399, with sales sometimes pushing the lower-end model below $2000.

The 9th-gen Intel Core i7 benchmarks around 1024 in single-core testing and 5385 in multi-core testing in a 16-inch MacBook Pro with 16GB of RAM. That's slightly lower than the A12Z in single-core, but clocks in higher in multi-core benchmarks.

Credit: Andrew O'Hara, AppleInsider

Keep in mind that benchmarks aren't always a reliable indicator of real-world performance. Whether or not they translate to speed and performance in your own setup is largely depends on how your workflow compares to the benchmark suite's calculations.

With that being said, these benchmarks do back up the fact that Apple's chip design and foundry have come a long way. The combination of design, whole-stack control, and foundry expertise have continuously pushed the industry toward faster and more efficient mobile processors. That trend isn't likely to stop at the Mac.

Past versions of Apple's A-series chips benchmarked at the lower end of what was available on the Mac. And although comparing the A12Z to the latest 16-inch MacBook Pro still illustrates an Intel performance advantage, it's clear that Apple Silicon is catching up, and who knows what Apple has in store for us.

The first of the Apple Silicon Macs are likely to make up the lower end of Apple's Mac lineup, as indicated by rumors that the first Mac to come with an A-series chip could be a 12-inch MacBook refresh. But Apple has already laid the groundwork for "Pro" Macs with Apple Silicon.

There are already high-performance ARM-based chips out there, mostly running in servers and delivering better performance-per-dollar and energy efficiency than Intel processors. While their market share is still paltry compared to Intel, the pace of performance upgrades and advancements in technology may just close that gap. With Apple moving its complete lineup of Macs to ARM-based Apple Silicon, it could further spur adoption by computer makers and server companies.

As indicated by the pace of Apple's A-series developments, a Pro Apple Silicon chip could very well run circles around a similar Intel chip -- especially when you consider how quickly the A-series has caught up to desktop performance. Also note that Apple Silicon Macs will have more robust cooling solutions than the iPads in the previous comparisons, meaning that thermal throttling could be less of an issue.

With all that in mind, it isn't hard to foresee a high-performing ARM chip in a Mac Pro somewhere down the road. When -- not if -- Apple Silicon chips built off Apple's A-series chip legacy end up in a MacBook Pro, they will in all probability kick off a new era of performance, efficiency and integration with Apple's wider ecosystem for the Mac.

Apple Macs have long used Intel chipsets, but that's due to change within the next few years.

Since the very first iPhone, Apple has been using ARM-based processors in its mobile devices. The company launched its first true A-series chip with the iPhone 4, which came equipped with the Apple A4 chip. Since then, Apple's proprietary chips have been breaking ground and stretching the limits of what is possible from ARM-derived processors in a mobile package.

Now that we know future Mac devices are going to sport Apple Silicon too, it's helpful to look back at how recent Apple A-series chips compare performance-wise to Macs with Intel processors in them. Here's how the A10 through the A12Z stacks up against similarly performing Intel chips.

A10 and A10X Fusion Chipset

Credit: Apple

The A10 Fusion chipset was first released on the iPhone 7 and iPhone 7 Plus in September 2016. Despite its age, the A10 Fusion can still keep up with many current tasks thanks to its power.

Per Geekbench 5, the 2.3GHz A10 Fusion clocks in with a single-core of 740 and a multi-core score of 1322.

With those scores, it means the A10 Fusion chipsets are roughly similar to the early 2016 12-inch MacBook, which Apple has since discontinued.

The 12-inch MacBook equipped with a 1.3GHz Intel Core m7 processor clocked in with a single-core score of 652 and a multi-core score of 1405. It retailed for $1,299 at the time of its release.

A10X Chipset

Credit: Apple

After the release of the A10 Fusion, Apple adapted the chip for its tablet lineup with the A10X Fusion chip. Throughout its life, it powered the 6th-generation and 10.2-inch iPad, the 10.5-inch iPad Pro, and the 2nd-generation 12.9-inch iPad Pro.

The device benchmarks pretty similarly to the A10 Fusion, though it comes in slightly higher. On an iPad, it clocks in with a single-core score of 755 and a multi-core score of 1403. It's quite a bit faster on the aforementioned iPad Pros, with single-core scores of 831 and multi-core scores of 2265. The A10X Fusion could be had for as low as $649 on an iPad Pro.

With those scores, the A10X Fusion is in the same ballpark as a 13-inch MacBook Pro model from 2017. The specific variant we're comparing is the mid-range configuration with an Intel Core i5 processor, which retailed for $1,499.

The aforementioned 13-inch MacBook Pro clocks in with a single-core Geekbench 5 score of 850 and a multi-core score of 1972, meaning it's actually slightly slower in multi-core performance despite being more expensive than the iPad Pro.

A11 Bionic Chipset

Credit: Apple

The A11 Bionic chip was introduced on the iPhone 8, iPhone 8 Plus and iPhone X in 2017. A dual-core processor, the A11 Bionic was also the first A-series chip to sport an Apple "Neural Engine" for A.I. and machine learning tasks.

On an iPhone X, the A11 Bionic came in with a 917 single-core and 2350 multi-core score in Geekbench 5 benchmark testing. While that device retailed for $999, the A11 Bionic could be found for cheaper in the iPhone 8 series.

The entry-level 2020 MacBook Air, equipped with an Intel Core i3-1000NG4, benchmarks similarly. It's a low-power 1.1GHz dual-core processor with Turbo Boost up to 3.2GHz.

The early 2020 MacBook Air (base model) equipped with the chipset has an average single-core score of 1076 and a multi-core score of 2842. The computer it comes in retails for $999.

A12 Bionic Chipset

Credit: Apple

The A12 Bionic, which first appeared on the iPhone XS, iPhone XS Max and iPhone XR, was Apple's first to be made with a 7nm chip process. (It also ended up in a non-X form in the 2019 iPad Air 3 and iPad mini.) The A12 could be had for $750 in an iPhone, or $399 in an iPad.

In an iPhone XS, the 2.5GHz A12 Bionic scored a 1106 and a 2687 in multi-core Geekbench 5 benchmark testing. In the latest iPad Air, benchmarks came in slightly higher with a single-core score of 1112 and a multi-core score of 2869.

That puts the A12 Bionic on roughly the same footing at the 2017 21.5-inch iMac equipped with a 3GHz Intel Core i5-7400 processor. That device started at $1,099.

In an iMac with 8GB of RAM, the Intel Core i5 scored a 1005 in single-core Geekbench 5 testing and a 3208 in multi-core benchmarking.

A13 Bionic

Credit: Apple

The A13 Bionic is currently Apple's latest iPhone chip, and it's installed in the iPhone 11, iPhone 11 Pro, iPhone 11 Pro Max and iPhone SE devices.

It's a 2.66 GHz, six-core processor. Per Geekbench 5 benchmarks, the A13 Bionic averages a single-core score of 1325 and a multi-core score of 3382. While the higher-tier iPhones pack it, you can get the A13 Bionic as cheap as $399 in Apple's 2020 iPhone SE.

If you want similar performance in a Mac, you'll probably want to take a look at the 13-inch MacBook Pro with an 8th-generation Intel Core i5-8257U processor. That MacBook processor is a 1.4GHz quad-core chip with Turbo Boost up to 3.9GHz, per Apple's specifications.

On Geekbench 5, it comes in lower than the iPhone in single-core scores but slightly higher in multi-core with 1012 and 3676, respectively. You can get that chip in an entry-level MacBook Pro for $1,299.

A12X and A12Z Bionic

Credit: Apple

There are two generations of iPad-specific A12 chips that Apple has released in the past two years: the A12X, which was installed in the 2018 iPad Pro models, and the A12Z, which powers the 2020 iPad Pro models, as well as the Apple Developer Transition Kit.

Both chips benchmark similarly on Geekbench 5, mostly due to the fact that they are essentially the same piece of silicon with slight modifications (such as an extra GPU core).

The A12X and A12Z Bionic both benchmark around 1115 in single-core testing, but they clock in as the fastest iOS-based devices in multi-core benchmarks with a high score of 4626. On an Apple Developer Transition Kit running Geekbench 5 natively, the scores are roughly similar with single-core scores around 1005 and multi-core scores around 4555. The A12Z retails for $799 in an 11-inch iPad Pro.

If you want similar single- and multi-core performance in an Intel-based chip, the way to get it is the mid-range 16-inch MacBook Pro with Intel Core i7 processor. It retails for $2,399, with sales sometimes pushing the lower-end model below $2000.

The 9th-gen Intel Core i7 benchmarks around 1024 in single-core testing and 5385 in multi-core testing in a 16-inch MacBook Pro with 16GB of RAM. That's slightly lower than the A12Z in single-core, but clocks in higher in multi-core benchmarks.

What this means for the Mac

Credit: Andrew O'Hara, AppleInsider

Keep in mind that benchmarks aren't always a reliable indicator of real-world performance. Whether or not they translate to speed and performance in your own setup is largely depends on how your workflow compares to the benchmark suite's calculations.

With that being said, these benchmarks do back up the fact that Apple's chip design and foundry have come a long way. The combination of design, whole-stack control, and foundry expertise have continuously pushed the industry toward faster and more efficient mobile processors. That trend isn't likely to stop at the Mac.

Past versions of Apple's A-series chips benchmarked at the lower end of what was available on the Mac. And although comparing the A12Z to the latest 16-inch MacBook Pro still illustrates an Intel performance advantage, it's clear that Apple Silicon is catching up, and who knows what Apple has in store for us.

The first of the Apple Silicon Macs are likely to make up the lower end of Apple's Mac lineup, as indicated by rumors that the first Mac to come with an A-series chip could be a 12-inch MacBook refresh. But Apple has already laid the groundwork for "Pro" Macs with Apple Silicon.

There are already high-performance ARM-based chips out there, mostly running in servers and delivering better performance-per-dollar and energy efficiency than Intel processors. While their market share is still paltry compared to Intel, the pace of performance upgrades and advancements in technology may just close that gap. With Apple moving its complete lineup of Macs to ARM-based Apple Silicon, it could further spur adoption by computer makers and server companies.

As indicated by the pace of Apple's A-series developments, a Pro Apple Silicon chip could very well run circles around a similar Intel chip -- especially when you consider how quickly the A-series has caught up to desktop performance. Also note that Apple Silicon Macs will have more robust cooling solutions than the iPads in the previous comparisons, meaning that thermal throttling could be less of an issue.

With all that in mind, it isn't hard to foresee a high-performing ARM chip in a Mac Pro somewhere down the road. When -- not if -- Apple Silicon chips built off Apple's A-series chip legacy end up in a MacBook Pro, they will in all probability kick off a new era of performance, efficiency and integration with Apple's wider ecosystem for the Mac.

Comments

Hopefully they can have a 25 W SoC that keeps the keyboard and top case cool while providing better performance than Intel systems. Actually, I think they can put the logic board behind the display by the hinge if it is long skinny like the iPad Pros. That'll remove the primary source of heat from the keyboard and keep it nice and cool at all times.

If A12Z is similar to i7 wouldn't Apple's A14 be similar to i9?

Behind the display? I doubt the fan and the heatsink will fit.

The new chip will most likely run hotter than the current A series since they will want it to be more powerful and don't forget the GPU! If there's a fan less version it will most likely be a 13" MBP.

I’d say they intentionally held back such as not to tip their hand. If you extrapolate the performance gains from A12 to A13, you can imagine where an A13X would have been, now add another generation, less concern for power/heat, and focus on desktop performance, and I’d expect people to be as blown away by the performance as they were when Apple baffled everyone moving the iPhone to a 64Bit platform...

What you propose is was MS did with the Surface Book. You'll have to sacrifice some inches in the screen, with the benefit that you mentioned. I think it could be possible with the new, smaller SoC's.

Imagine what Apple can do just in a MacBook alone, let alone in a desktop like iMac.

Recent stories here and elsewhere are kind of focused on the chips themselves because that's where the (tiny amount of available) information is right now, but there's really four keys to future Macs: first, the specially-designed Mac-centric SoC; second, the optimized motherboard and other mechanical components (we've been enjoying some of this part for years now, which is why we're so far ahead of PC makers on things like TB3/USB-C/USB4); third, software compiled specifically to take advantage of this custom hardware (in particular, I foresee much greater expansion on multi-tasking for all but the most basic software); and four, new chassis designs again fully in harmony with the chip, graphics, thermals, and support systems.

Intel has been great for Apple, and often very accommodating to Apple's specific desires (especially given the size of the Mac market, which is still small). But Apple Silicon (please note: not silicone!) is made not only with an awareness of hardware requirements but also the specific ways Mac users work with software, neither of which Intel can really design for. Because of the potential this opens up, I think Apple will continue to work on bringing more components in-house (like wireless/5G) and forming partnerships with third-parties where they can get custom-designed parts for its particular and in some cases unique needs.

Kudos to Mike P for the rundown, though this is really only the beginning of a tale mostly yet to be revealed. Specs and comparisons are fun, but at the end of the day the truly remarkable thing about all this is that Apple has been planning a brilliant revival of the Mac -- by far their least-popular "computer" product, let's not forget -- to keep it relevant and even exciting in the current age of mobile and wearable domination. I cannot wait to see what Apple Silicon running new Apple hardware can do, how much room for innovation they've opened up, and specifically (though I'm not the target for it) what high-end Apple Macs are going to be able to do. I'm with Jean-Louis Gassée in thinking that some major surprises are still ahead of us, including some that will benefit the entire industry, directly or indirectly.

Bashing Intel is no news. Apple needs to beat AMD now, not Intel and this is much less likely given how perfect the recent AMD Notebooks have been considering the relevant metrics.

Not that I think they would do it. It's just the transition to Apple Silicon represents a big opportunity to redesign a laptop inside and outside, and I hope Apple takes it. Apple Silicon logic boards will be smaller than Intel boards by quite a bit, and with lower power, the batteries can get smaller too. This provides some opportunities for design. They can do some pretty wild things.

Yes, for an iPad, no more than 7 to 8 W. It's a handheld device and that should automatically limit it to passive cooling from the case without it being uncomfortable to touch. But on a laptop that only has about say 3 mm of height for a fan and heatsink, I think 15 W is definitely possible. Apple achieves 15 W with about 8 mm of height an one fan for the 2 port. A bigger fan, a bigger heat sink, more airflow could probably achieve double that. But Apple simply isn't going to do that or really doesn't want to so it. They want to get away from having to design around hot components in their machines. So, if they have a thin and light laptop, it is likely going to use a lower Watt SoC that outperforms Intel and AMD thin and light laptops, that use hotter components.

The decreased logic board area and decreased battery capacities does offer some interesting things though. If the board gets small enough, there may be enough room for a keyboard with 3 to 4 mm of travel. A nice clickity-clackity 4 mm travel laptop keyboard would be very very interesting. The dual display clamshell or folding display clamshell can be 6 mm thick unfolded, 12 mm closed. There are going to be a few Lakefield laptops like this, but Apple should be able to crush them in terms of performances and the number of touchscreen apps too.

Hopefully, one of their big priorities is to have none of their Apple silicon laptops be uncomfortable to the touch. No more than 85 °F or something like that. They'd rather use a 10 W SoC than a 20 W SoC in a MBP13, or a 25 W SoC than a 50 W SoC in a MPB16, if they can help it.