If US lawmakers are good at anything, it's failing at technology

U.S. lawmakers are not just technologically illiterate -- they're tech-incompetent. In a world as reliant on tech hardware, software, and services as ours, that's dangerous.

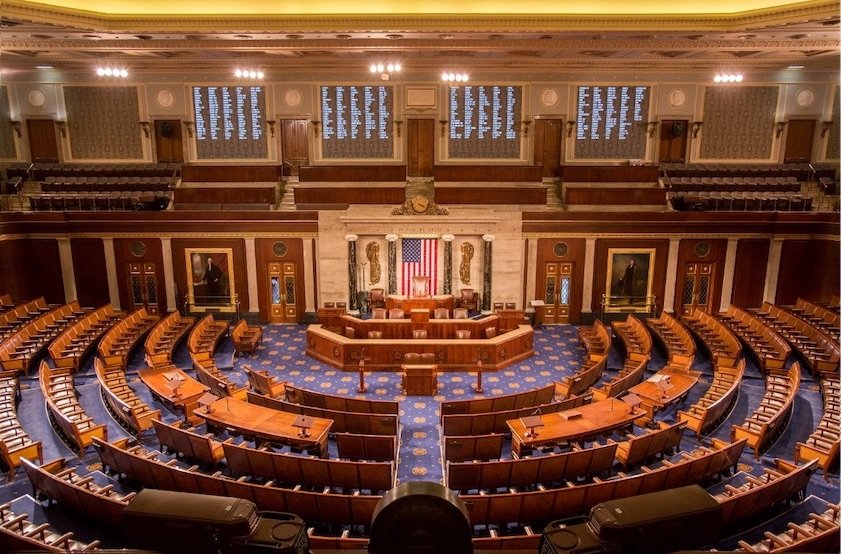

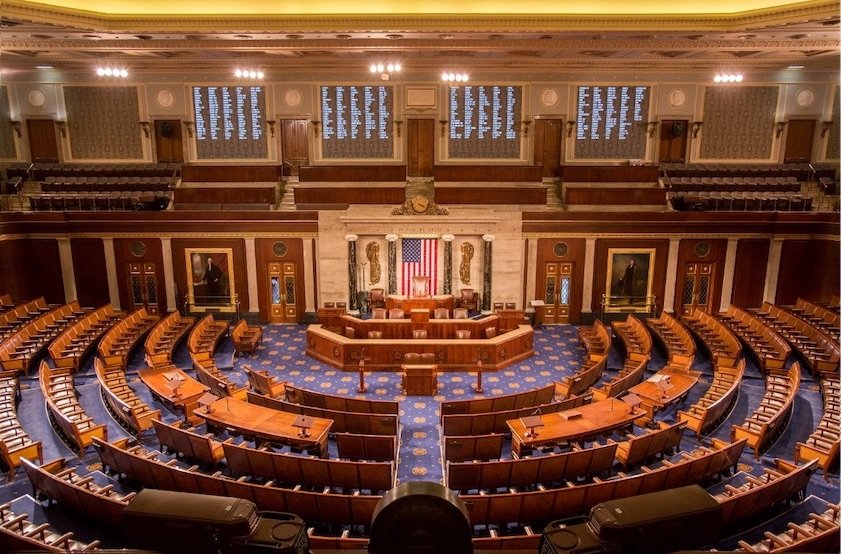

US Capitol building at night

Members of Congress from both sides of the aisle, and governments overseas have repeatedly shown their lack of knowledge about essential tech topics. That hampers their ability to enact real change and undoubtedly leads them to draft ineffective and sometimes meaningless legislation.

Three recent examples, one of which is not from the US, perfectly illustrates this point.

Beyond the fact that this is likely just political grandstanding with a hint of xenophobia, the so-called Defending Americans from Authoritarian Digital Currencies Act also doesn't make a lot of sense</>.

According to the lawmakers, the Chinese government will use the currency to "control and spy on anyone who uses it." The trio of politicians called the potential support for digital yuan on U.S. app stores a "major financial and surveillance risk."

The problem is that no one in the U.S. is going to use digital yuan in their day-to-day life to make purchases or buy subscriptions on the App Store. There's absolutely no reason to use a "digital yuan" to buy an app when you could purchase it in U.S. dollars with your attached credit card.

Additionally, there's also no support for it. Apple accepts payments for apps and in-app purchases in national currency. In the U.S., it's the dollar. You can't currently buy an app using Bitcoin, Dogecoin, or any other digital currency.

App and in-app purchases are processed by Apple without personal information.

More than that, all purchases made through the App Store are routed through Apple's payment processing systems. Payment receipts sent by Apple to developers don't include personal information, so there isn't a real risk of mass financial surveillance of U.S. citizens.

There are valid concerns about the privacy and security implications of digital yuan -- for Chinese citizens in China. No one is buying Candy Crush lives using digital yuan in the U.S. It isn't likely that this type of scenario will play out anytime soon, despite what crypto enthusiasts might tell you.

It's a bizarre and useless piece of legislation, and it underscores the lack of tech literacy among U.S. lawmakers. However, there are other bills and moves to regulate tech giants that may be more grounded in reality, but only offer oversimplified solutions because of a lack of concrete knowledge of how tech works.

Take the American Choice and Innovation Act, which Sen. Amy Klobuchar recently revised to account for concerns about its sweeping changes. While antitrust concerns are valid, bills that are too broad could a slew of unintended side effects.

The bill is also incredibly murky on how it defines dominant platforms and how the regulations will be enforced. A better understanding of the tech ecosystem, and how individual companies operate, would result in a clearer bill with better rules.

Of course, tech illiteracy isn't exclusive to the U.S. The European Union, for example, is pushing toward a mandate to require all devices use a USB-C port. The major problem there is that enshrining a specific piece of technology into law doesn't account for the pace of advancement.

Before USB-C was a de facto standard among tech giants, the mandate was -- and still is, today -- micro USB. It's not a stretch to say that USB-C will eventually be phased out for something else, and could even be replaced by a portless solution. Making USB-C the standard through law doesn't make any sense.

And these are just the three most recent examples. There are so many more.

More than a decade later, not a lot has changed. From Google CEO Sundar Pichai being grilled about an Apple iPhone to a lawmaker not understanding that Facebook runs ads to make money, the tech illiteracy among U.S. legislators is striking -- and embarrassing.

During a Congressional hearing, that lack of competence results in lawmakers asking stupid questions that aren't relevant to any topic at hand. It can also make it easier for tech giants to weasel out of uncomfortable -- and essential -- lines of inquiry.

In an online environment whose main currency is snark, these examples might be funny. But they also underscore the embarrassing lack of knowledge many elected officials have about even the most basic of technology concepts.

The harmful effects extend beyond the hearing too. Without at least a baseline of tech literacy and without good answers to important questions from tech executives, effective legislation is a moonshot.

There are undoubtedly very clear lines of partisan disagreement when it comes to tech legislation. One side is worried about censorship, for example, while the other side is worried about misinformation. You would think there could be common ground somewhere in that Venn diagram, but it's clear that there isn't.

The issue of hyper-partisanship is only exacerbated by the fact that the debate around technology platforms is so often divorced from reality. Without a firm understanding of something like Section 230 or how tech giant business models are set up, the debate between lawmakers will be based on political talking points that have little -- if any -- basis in fact.

Lawmakers can't hold tech executives to account if they are ignorant about the details.

There's also the issue of nebulousness, as is the case with Right to Repair laws. Lawmakers, advocates, citizens, and companies can't agree on a comprehensive solution to calls for Right to Repair because there isn't a set-in-stone definition of what that could look like.

It might be easier to come to a joint agreement on issues -- and it would certainly be easier to write a definition -- if all lawmakers had the knowledge and resources to become better acquainted with the tech topics they're tackling.

If a senator doesn't even know how Facebook makes money, they're not going to be able to write effective laws that keep the company from abusing user data or letting disinformation run unchecked.

The OTA was a bipartisan office governed by 12 members of Congress -- six Republicans and six Democrats. It had a staff of 143 people who were mostly scientists, with a smattering of support people.

It cost the federal government about $22 million per year in the early '90s. In 1995, the government dissolved the office as "wasteful," with arguments that government officials were more than capable enough to understand and govern fairly on the issues and technologies of the day.

Of course, government officials weren't even capable of understanding technical topics without the OTA in 1995. As the years have passed, the problem has only gotten worse.

The U.S. once had an office dedicated to educating lawmakers about tech issues, but it was dissolved in 1995.

There are still some people doing a similar type of work as the OTA did, but it's mostly a skeleton staff of non-scientists at the Government Accountability Office. Beyond not being scientists, this group is underfunded, understaffed, and unprepared to handle the increasingly complex matters at hand.

Of course, it isn't clear how much the concept manned by a skeleton crew helps with the problem if that inability to deal with complex scientific or technological matters is willful. The European Parliamentary Technology Assessment (EPTA) performs roughly the same tasks, with roughly the same manning, and it doesn't seem to help decisions there either.

It also isn't clear if the government's lack of ability to legislate tech issues effectively is willful, or just incompetence.

It's undoubtedly a bad idea to let massive multinational corporations like Facebook or Google go unchecked, particularly when many of them have long track records of scandals, abuses, and other controversies. Antitrust legislation here is probably warranted, as long as it's grounded in knowledge.

Solving political partisanship and the lack of agreement on how to correct specific issues is obviously going to be harder -- if not impossible -- to fix, but the lack of basic tech understanding among politicians from both sides of the aisle is only making the situation insurmountable.

Doing something is important, but it's essential to understand the ins and outs of a specific area before you go about effectively legislating it. Ignorance on this topic is only going to result in bad laws that can negatively affect the rest of us -- and that might not even do anything to rein in Big Tech.

Given the U.S. government's history with technological incompetence, however, it's a certainty that we'll continue to see bad laws coming from the halls of Congress.

Read on AppleInsider

US Capitol building at night

Members of Congress from both sides of the aisle, and governments overseas have repeatedly shown their lack of knowledge about essential tech topics. That hampers their ability to enact real change and undoubtedly leads them to draft ineffective and sometimes meaningless legislation.

Three recent examples, one of which is not from the US, perfectly illustrates this point.

The latest examples of technological stupidity

On Friday, U.S. Senators Tom Cotton, Mike Braun, and Marco Rubio introduced a new bill seeking to ban app stores from supporting transactions in China's digital yuan -- or even hosting apps that use the currency.Beyond the fact that this is likely just political grandstanding with a hint of xenophobia, the so-called Defending Americans from Authoritarian Digital Currencies Act also doesn't make a lot of sense</>.

According to the lawmakers, the Chinese government will use the currency to "control and spy on anyone who uses it." The trio of politicians called the potential support for digital yuan on U.S. app stores a "major financial and surveillance risk."

The problem is that no one in the U.S. is going to use digital yuan in their day-to-day life to make purchases or buy subscriptions on the App Store. There's absolutely no reason to use a "digital yuan" to buy an app when you could purchase it in U.S. dollars with your attached credit card.

Additionally, there's also no support for it. Apple accepts payments for apps and in-app purchases in national currency. In the U.S., it's the dollar. You can't currently buy an app using Bitcoin, Dogecoin, or any other digital currency.

App and in-app purchases are processed by Apple without personal information.

More than that, all purchases made through the App Store are routed through Apple's payment processing systems. Payment receipts sent by Apple to developers don't include personal information, so there isn't a real risk of mass financial surveillance of U.S. citizens.

There are valid concerns about the privacy and security implications of digital yuan -- for Chinese citizens in China. No one is buying Candy Crush lives using digital yuan in the U.S. It isn't likely that this type of scenario will play out anytime soon, despite what crypto enthusiasts might tell you.

It's a bizarre and useless piece of legislation, and it underscores the lack of tech literacy among U.S. lawmakers. However, there are other bills and moves to regulate tech giants that may be more grounded in reality, but only offer oversimplified solutions because of a lack of concrete knowledge of how tech works.

Take the American Choice and Innovation Act, which Sen. Amy Klobuchar recently revised to account for concerns about its sweeping changes. While antitrust concerns are valid, bills that are too broad could a slew of unintended side effects.

The bill is also incredibly murky on how it defines dominant platforms and how the regulations will be enforced. A better understanding of the tech ecosystem, and how individual companies operate, would result in a clearer bill with better rules.

Of course, tech illiteracy isn't exclusive to the U.S. The European Union, for example, is pushing toward a mandate to require all devices use a USB-C port. The major problem there is that enshrining a specific piece of technology into law doesn't account for the pace of advancement.

Before USB-C was a de facto standard among tech giants, the mandate was -- and still is, today -- micro USB. It's not a stretch to say that USB-C will eventually be phased out for something else, and could even be replaced by a portless solution. Making USB-C the standard through law doesn't make any sense.

And these are just the three most recent examples. There are so many more.

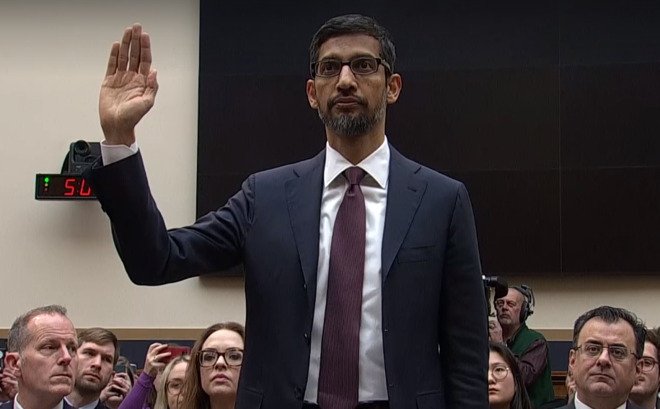

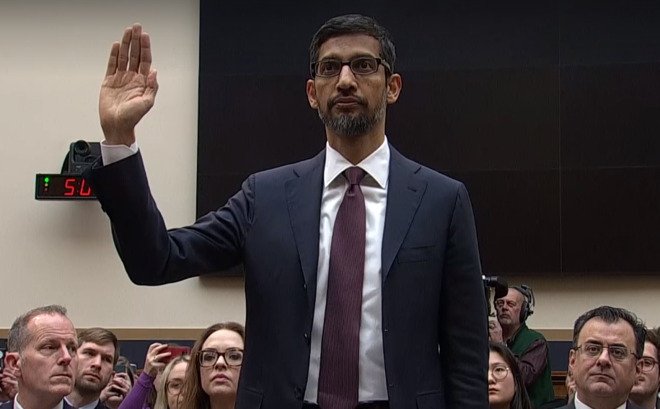

If Congressional hearings on technology are known for anything, it's lawmaker gaffes

Back in June 2006, then-Senator Ted Stevens of Alaska likened the internet to a "series of tubes" -- illustrating his minimal understanding of how it worked. The phrase was widely ridiculed, mainly because Stevens led the Senate committee responsible for regulating the internet.More than a decade later, not a lot has changed. From Google CEO Sundar Pichai being grilled about an Apple iPhone to a lawmaker not understanding that Facebook runs ads to make money, the tech illiteracy among U.S. legislators is striking -- and embarrassing.

During a Congressional hearing, that lack of competence results in lawmakers asking stupid questions that aren't relevant to any topic at hand. It can also make it easier for tech giants to weasel out of uncomfortable -- and essential -- lines of inquiry.

In an online environment whose main currency is snark, these examples might be funny. But they also underscore the embarrassing lack of knowledge many elected officials have about even the most basic of technology concepts.

The harmful effects extend beyond the hearing too. Without at least a baseline of tech literacy and without good answers to important questions from tech executives, effective legislation is a moonshot.

Incompetence is just gasoline on the fire of division and uncertainty

Of course, ignorance is not the only obstacle to practical and grounded tech legislation in the U.S. There's also the problem that lawmakers from both political camps can't agree on how to go about rules to curb Big Tech's power.There are undoubtedly very clear lines of partisan disagreement when it comes to tech legislation. One side is worried about censorship, for example, while the other side is worried about misinformation. You would think there could be common ground somewhere in that Venn diagram, but it's clear that there isn't.

The issue of hyper-partisanship is only exacerbated by the fact that the debate around technology platforms is so often divorced from reality. Without a firm understanding of something like Section 230 or how tech giant business models are set up, the debate between lawmakers will be based on political talking points that have little -- if any -- basis in fact.

Lawmakers can't hold tech executives to account if they are ignorant about the details.

There's also the issue of nebulousness, as is the case with Right to Repair laws. Lawmakers, advocates, citizens, and companies can't agree on a comprehensive solution to calls for Right to Repair because there isn't a set-in-stone definition of what that could look like.

It might be easier to come to a joint agreement on issues -- and it would certainly be easier to write a definition -- if all lawmakers had the knowledge and resources to become better acquainted with the tech topics they're tackling.

If a senator doesn't even know how Facebook makes money, they're not going to be able to write effective laws that keep the company from abusing user data or letting disinformation run unchecked.

There used to be an office in the U.S. designed to help with this, but it is long gone

The U.S. once had a solution to tech illiteracy. It established the Office of Technology Assessment in 1972 with the goal of educating and briefing both the House and Senate on the complex scientific and technical issues of the day. It was instrumental in the early digital distribution of government documents to not just the feds, but to the public as well.The OTA was a bipartisan office governed by 12 members of Congress -- six Republicans and six Democrats. It had a staff of 143 people who were mostly scientists, with a smattering of support people.

It cost the federal government about $22 million per year in the early '90s. In 1995, the government dissolved the office as "wasteful," with arguments that government officials were more than capable enough to understand and govern fairly on the issues and technologies of the day.

Of course, government officials weren't even capable of understanding technical topics without the OTA in 1995. As the years have passed, the problem has only gotten worse.

The U.S. once had an office dedicated to educating lawmakers about tech issues, but it was dissolved in 1995.

There are still some people doing a similar type of work as the OTA did, but it's mostly a skeleton staff of non-scientists at the Government Accountability Office. Beyond not being scientists, this group is underfunded, understaffed, and unprepared to handle the increasingly complex matters at hand.

Of course, it isn't clear how much the concept manned by a skeleton crew helps with the problem if that inability to deal with complex scientific or technological matters is willful. The European Parliamentary Technology Assessment (EPTA) performs roughly the same tasks, with roughly the same manning, and it doesn't seem to help decisions there either.

It also isn't clear if the government's lack of ability to legislate tech issues effectively is willful, or just incompetence.

Reining in tech giants is necessary, but it needs to be grounded in knowledge

Concentrations of power are dangerous. That's the idea behind monopoly laws and the system of checks and balances in the U.S. government itself. However, going after concentrations of power without even the slightest bit of literacy on the relevant topics is dangerous, too.It's undoubtedly a bad idea to let massive multinational corporations like Facebook or Google go unchecked, particularly when many of them have long track records of scandals, abuses, and other controversies. Antitrust legislation here is probably warranted, as long as it's grounded in knowledge.

Solving political partisanship and the lack of agreement on how to correct specific issues is obviously going to be harder -- if not impossible -- to fix, but the lack of basic tech understanding among politicians from both sides of the aisle is only making the situation insurmountable.

Doing something is important, but it's essential to understand the ins and outs of a specific area before you go about effectively legislating it. Ignorance on this topic is only going to result in bad laws that can negatively affect the rest of us -- and that might not even do anything to rein in Big Tech.

Given the U.S. government's history with technological incompetence, however, it's a certainty that we'll continue to see bad laws coming from the halls of Congress.

Read on AppleInsider

Comments

I'm sure this or that politician is actually very knowledgeable about certain things, as much as any well studied and educated person can be, but legislation isn't some collegiate discussion involving facts and proper courses of action. It's a knockdown drag-out fight of acquiring the necessary votes in a room with a 48:48:4 split of yes:no:whoknows. The yes:no decision making is not based on some ethical calculus in a topic. It's "how does it effect my next election cycle".

Ultimately, you can probably blame the electorate for electing these folks. That's what the majority of voters wanted. To change it, the voters have to vote different.

Braun was born in Jasper, Indiana, on March 24, 1954.[4] He graduated from Jasper High School. Braun was a three-sport star athlete; he married his high school sweetheart, Maureen,[5] who was a cheerleader.[6] He attended the all-male Wabash College, where he was a member of Phi Delta Theta fraternity and graduated summa cum laude with a bachelor's degree in economics, and Harvard Business School, where he earned an MBA.

Cotton was accepted to Harvard College after graduating from high school in 1995. At Harvard, he majored in government and was a member of the editorial board of The Harvard Crimson, often dissenting from the liberal majority.[5] In articles, Cotton addressed what he saw as "sacred cows" such as affirmative action.[6] He graduated with an A.B. magna cum laude in 1998 after only three years of study. Cotton's senior thesis focused on The Federalist Papers.[4]

After graduating from Harvard College in 1998, Cotton was accepted into a master's program at Claremont Graduate University. He left in 1999, saying that he found academic life "too sedentary", and instead enrolled at Harvard Law School.[4] He graduated with a J.D. degree in 2002.

This is the continental divide between Congress and HighTech.

Many mainland Chinese are using a message app called WeChat. You can do a lot more thing than WhatsApp or iMessage. People can put money in their WeChat account and e-transfer money to other or use it to pay for services and buy things online.

So preemptive to stop using digital yuan in US is actually a good thing.

Today with global warming, everyone is threatened, everyone needs to act on it to forge a path to minimize human misery. We live in a world today where "survivability" has become a question, and not enough people think of the future 50 years out. Most people can't even think about tomorrow. It's ok if the USA disintegrates into 3 or 4 separate countries as long as we are treading a path to survivability. Failing will really hurt a lot of people this go around. It's really important now, to move in one direction, but alas no. So, heading towards the cliff we go, doing what always has been done.

I thought we were done with nuclear MAD, but here we are, there's always going to be some leader who plays the game, and they will be one who thinks the outcome will fine. Too bad we couldn't decommission 99% of the nukes. That remaining 1% would be bad enough.

That is a fact, but just to add to it a little bit: The office was killed as part of the Republican Party takeover of the House of Representatives that year after winning a majority in the 1994 midterms. House Republicans saw the OTA as, "as duplicative, wasteful, and biased against their party. During the 1994 elections, then-Representative Newt Gingrich (R–GA) vowed to kill the office if his party took control of Congress, which it did. At the time of OTA's dismantling in 1995, it had about 140 staffers and a budget of roughly $21 million." (Source: https://www.science.org/content/article/house-democrats-move-resurrect-congress-s-science-advisory-office)

I'll stop there, but just wanted to be clear who is to blame for the OTA's disappearance. As that article states, current House Democrats are trying to bring the office back.

There once was a very fat radio personally on the right who made fun of the Internet, Wind and Solar Power his minions followed along he’s gone and they aren’t laughing anymore, however they do still laugh at High Speed Rail the rest of the world doesn’t.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhXgVBbEHQg

We need to git to work……