Apple was cautious when it shifted to Intel, and an ARM Mac migration will be no different...

Apple took a convoluted 20-year journey to shift the Mac to Intel processors, and it isn't jumping into ARM on a whim. Here's what the previous journey looked like.

Steve Jobs welcomes Intel to the Mac in 2005

There have been rumors for a decade that Apple will move the Mac from Intel to ARM processors. It's no surprise that if it happens, Apple will have spent a time getting the ARM Mac ready, but we might discover that Apple has been thinking about it for a lot longer.

That's because the 2005 move to Intel had its roots going back far, far further than was suspected at the time.

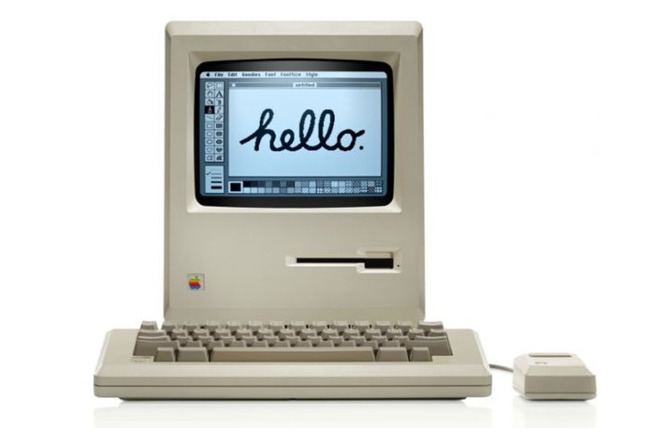

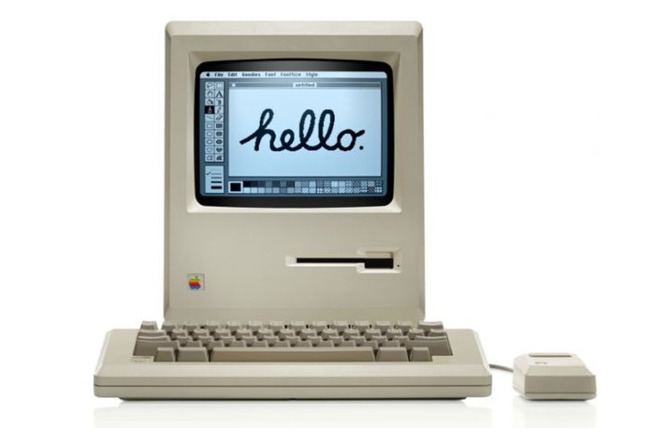

If you are truly a long-time Mac user, then you can imagine how strange it must have been when the familiar startup chime first came out of an Intel PC. But it wasn't in 2005 as Steve Jobs announced was announcing the first Intel Macs, though. Instead, the familiar Mac startup was first shown on a PC all the way back on December 4, 1992.

And even that wasn't the start of Apple's move to Intel.

Bill Gates in 2020

In June 1985, Gates wrote a multi-page memo to then-CEO John Sculley detailing why he thought Apple should license the Mac operating system. While he wrote praisingly about the Intel architecture in IBM PCs, he didn't specify that he meant the Mac should run it.

Apple's own Dan Eilers did. Apple didn't take Gates up on his offer of helping out, but the company did task Eilers, then its director of strategic investment, with looking into it. He strongly proposed that Apple moved to Intel and he wasn't alone.

Larry Tesler, inventor of copy-and-paste on computers, revealed in 2011 that the whole engineering team had wanted the move.

"We had actually tried a few years before to port the MacOS to Intel, but there was so much machine code still there, that to make it be able to run both, it was just really really hard," he said.

"And so a number of the senior engineers and I got together and we recommended that first we modernize the operating system, and then we try to get it to run on Intel, initially by developing our own in-house operating system which turned out to be one of these projects that just grew and grew and never finished."

Also in the team at this time, and very much on board with an Intel move, was Alan Kay, practically a legend in computing. His argument, as quoted in Owen Linzmayer's "Apple Confidential 2.0," was that what made the Mac special was its operating system, and its software.

"When you're in the software business you have to run on every platform," Kay says he told Apple management. "So you must put the Mac operating system on the PC and put it on Sun workstations and put it on everything else because that's what you do when you're in the software business, right?"

Kay called this "probably the largest battle I lost here at Apple," and the company did not move to Intel in 1985. It tried to hammer out a deal in 1987, but the company did come close to it with the now forgotten Apollo Computer of Massachusetts.

The two companies did many collaborations, but this one would've seen the Mac operating system licensed to Apollo. If John Sculley hadn't decided Apollo wasn't going to stick around much longer, Apple would've had its first clone then and surely Intel machines would've followed.

The original Mac ran on a Motorola 68000 processor, but even shortly afterwards, Apple engineers wanted a move to Intel

As it is, it took until August 1990 before Dan Eilers tried again. He was even more insistent than Bill Gates had been, and presented what is reportedly a 112-page memo to management to try and sell the concept.

Whether it was Novell being convincing in its desire to license the Mac OS to run on Intel, or Eilers' making a better case, Apple started to move to Intel on February 14, 1992. At John Sculley's direction, the project was started and it was called "Star Trek."

The project was called that because it was also known as taking the Mac "where no Mac has gone before," into Intel territory. Bill Gates wasn't impressed. Maybe because it was seven years after he'd suggested it, he called Apple running the Mac on Intel as being "like putting lipstick on a chicken."

It was expensive lipstick. Apple and Novell together put four engineers on the project, headed by Chris DeRossi. On top of their unknown salaries, the four were promised a bonus if they could get the Mac running successfully on a PC. The bonuses, according to Linzmayer, ranged from $16,000 to $25,000.

In today's money, that's between $30,000 and $45,700, and the team did it. Or at least, they did it enough to get those bonuses and reportedly spend a lot of them on a doubtlessly deserved holiday.

DeRossi and Apple's vice president of software engineering, Roger Heinen, presented the results on December 4, 1992. That's when the first Intel Mac started up, complete with its "Welcome to Macintosh" front screen.

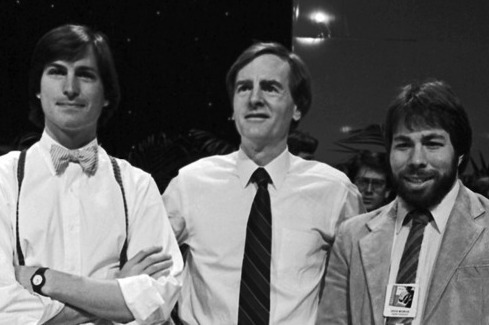

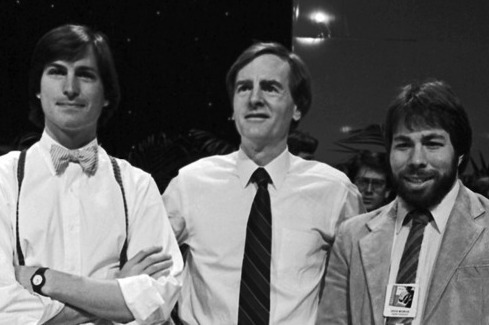

L-R: Steve Jobs, John Sculley, Steve Wozniak

What the team had done was get System 7.1 running on a PC -- but in truth it was a little more basic than that. Not all of the system was running, for one thing, but the chief issue was that it was only System 7.1 that would run at all. No apps did.

Unfortunately, John Sculley was on his way out when that demo happened. His replacement Michael Spindler didn't agree that licensing an Intel version of the Mac was a good idea. Plus, one of the two demonstrators, Roger Heinen, left Apple and went to work for Microsoft.

Spindler didn't cancel the project right away, but he might as well have. The original team of four had become one of 18, and then as Sculley left and Apple's Advanced Technology Group took over the project, it became 50.

Today Apple might well put 50 people working on a project, but back then, it was an expensive proposition. Especially so when Apple was then successfully committing to the PowerPC. And, especially when the 50 were reportedly engaged mostly in writing proposals instead of code.

Consequently, they were an easy target when Spindler needed to cut costs. And in June 1993, the "Star Trek" project was cancelled and no more work was done on that move to Intel.

According to Linzmayer, Jobs said this at an analyst meeting conference call, but beyond that account, we couldn't confirm the quote. If it is accurate, though, then something big changed right after it -- and it's probably to do with that phrase "road map."

Ultimately, Jobs would say the opposite at the launch of the transition to Intel, that PowerPC just didn't have the future Apple needed. Internally, though, Jobs or at least enough key personnel within Apple had been suspecting this for some time.

Around the year 2000, Apple began working on what would become the successful move. "Mac OS X has been leading a secret double life for the past five years," revealed Steve Jobs at the 2005 launch.

"There have been rumors to this effect," he continued, to laughter from a knowing WWDC 2005 audience who may had been reading half a decade's worth of rumors about it on AppleInsider. Jobs showed a slide marking the precise building at Apple's Infinite Loop campus where the work took place. "Right there, we've had teams doing the just-in-case scenario."

"Our rule has been that our designs for OS X must be processor independent," he said. "And that every project must be built for both the PowerPC and Intel processors. So today for the first time, I can confirm the rumors that every release of Mac OS X has been compiled for both PowerPC and Intel. This has been going on for the last five years."

Specifically, it had been going on since the release of Mac OS X Cheetah, which was released to the public on March 21, 2001.

Those first projects may have failed to move the Mac over to Intel, but once Apple truly committed to doing it, the company worked very quickly and very efficiently. That transition of the entire Mac lineup was incredibly smooth, and that's one reason why we can make some assumptions about the move to ARM.

First, it's been well and probably very long-planned. That's both in terms of the technology -- you can be certain that there are ARM-based Macs in Apple Park right now -- but also in terms of the transition.

What may be the most significant lesson from the Intel move, though, comes in that quote from Steve Jobs. "Our rule has been that our designs for OS X must be processor independent."

Having separated out the operating system so that it could sit atop either PowerPC or Intel, it seems unlikely that Apple will have ever decided to undo that. The current macOS is probably in a similar position and that means it won't need rewriting to work on ARM.

Apps will need work, as we saw in the Intel move, and even before that with the transition to PowerPC. Where the '90s project was a gigantic rewriting of the operating system to get it to work on Intel's processors, Apple has set the table with moves it has made for the last two decades to try and make that migration dramatically easier.

Or at least, easier for Apple. Regardless of the underpinnings of the operating system, it is still going to be the case that developers will shoulder a large burden. That will mean some developers having more complex jobs to do than others.

Users left in the cold with apps that don't make the transition won't benefit. But, the majority of the Mac using base, especially those yet to come, will see big benefits, though.

Keep up with AppleInsider by downloading the AppleInsider app for iOS, and follow us on YouTube, Twitter @appleinsider and Facebook for live, late-breaking coverage. You can also check out our official Instagram account for exclusive photos.

Steve Jobs welcomes Intel to the Mac in 2005

There have been rumors for a decade that Apple will move the Mac from Intel to ARM processors. It's no surprise that if it happens, Apple will have spent a time getting the ARM Mac ready, but we might discover that Apple has been thinking about it for a lot longer.

That's because the 2005 move to Intel had its roots going back far, far further than was suspected at the time.

If you are truly a long-time Mac user, then you can imagine how strange it must have been when the familiar startup chime first came out of an Intel PC. But it wasn't in 2005 as Steve Jobs announced was announcing the first Intel Macs, though. Instead, the familiar Mac startup was first shown on a PC all the way back on December 4, 1992.

And even that wasn't the start of Apple's move to Intel.

The first steps

The original Macintosh was launched on January 24, 1984, and ran on the Motorola 68000 processor. It wasn't an immediate success, though, and that's partly because it expensive, partly because it was slow. By 1985, Microsoft's Bill Gates was calling it a failure -- and he was telling Apple how to fix it.

Bill Gates in 2020

In June 1985, Gates wrote a multi-page memo to then-CEO John Sculley detailing why he thought Apple should license the Mac operating system. While he wrote praisingly about the Intel architecture in IBM PCs, he didn't specify that he meant the Mac should run it.

Apple's own Dan Eilers did. Apple didn't take Gates up on his offer of helping out, but the company did task Eilers, then its director of strategic investment, with looking into it. He strongly proposed that Apple moved to Intel and he wasn't alone.

Larry Tesler, inventor of copy-and-paste on computers, revealed in 2011 that the whole engineering team had wanted the move.

"We had actually tried a few years before to port the MacOS to Intel, but there was so much machine code still there, that to make it be able to run both, it was just really really hard," he said.

"And so a number of the senior engineers and I got together and we recommended that first we modernize the operating system, and then we try to get it to run on Intel, initially by developing our own in-house operating system which turned out to be one of these projects that just grew and grew and never finished."

Also in the team at this time, and very much on board with an Intel move, was Alan Kay, practically a legend in computing. His argument, as quoted in Owen Linzmayer's "Apple Confidential 2.0," was that what made the Mac special was its operating system, and its software.

"When you're in the software business you have to run on every platform," Kay says he told Apple management. "So you must put the Mac operating system on the PC and put it on Sun workstations and put it on everything else because that's what you do when you're in the software business, right?"

Kay called this "probably the largest battle I lost here at Apple," and the company did not move to Intel in 1985. It tried to hammer out a deal in 1987, but the company did come close to it with the now forgotten Apollo Computer of Massachusetts.

The two companies did many collaborations, but this one would've seen the Mac operating system licensed to Apollo. If John Sculley hadn't decided Apollo wasn't going to stick around much longer, Apple would've had its first clone then and surely Intel machines would've followed.

The original Mac ran on a Motorola 68000 processor, but even shortly afterwards, Apple engineers wanted a move to Intel

As it is, it took until August 1990 before Dan Eilers tried again. He was even more insistent than Bill Gates had been, and presented what is reportedly a 112-page memo to management to try and sell the concept.

Apple gets bold

It was around this time that Windows 3 came out, and in 1992 would become a real threat to Apple with the much improved Windows 3.1. Early in 1992, though, Apple was not the only company looking under threat -- so was Novell.Whether it was Novell being convincing in its desire to license the Mac OS to run on Intel, or Eilers' making a better case, Apple started to move to Intel on February 14, 1992. At John Sculley's direction, the project was started and it was called "Star Trek."

The project was called that because it was also known as taking the Mac "where no Mac has gone before," into Intel territory. Bill Gates wasn't impressed. Maybe because it was seven years after he'd suggested it, he called Apple running the Mac on Intel as being "like putting lipstick on a chicken."

It was expensive lipstick. Apple and Novell together put four engineers on the project, headed by Chris DeRossi. On top of their unknown salaries, the four were promised a bonus if they could get the Mac running successfully on a PC. The bonuses, according to Linzmayer, ranged from $16,000 to $25,000.

In today's money, that's between $30,000 and $45,700, and the team did it. Or at least, they did it enough to get those bonuses and reportedly spend a lot of them on a doubtlessly deserved holiday.

DeRossi and Apple's vice president of software engineering, Roger Heinen, presented the results on December 4, 1992. That's when the first Intel Mac started up, complete with its "Welcome to Macintosh" front screen.

L-R: Steve Jobs, John Sculley, Steve Wozniak

What the team had done was get System 7.1 running on a PC -- but in truth it was a little more basic than that. Not all of the system was running, for one thing, but the chief issue was that it was only System 7.1 that would run at all. No apps did.

Unfortunately, John Sculley was on his way out when that demo happened. His replacement Michael Spindler didn't agree that licensing an Intel version of the Mac was a good idea. Plus, one of the two demonstrators, Roger Heinen, left Apple and went to work for Microsoft.

Spindler didn't cancel the project right away, but he might as well have. The original team of four had become one of 18, and then as Sculley left and Apple's Advanced Technology Group took over the project, it became 50.

Today Apple might well put 50 people working on a project, but back then, it was an expensive proposition. Especially so when Apple was then successfully committing to the PowerPC. And, especially when the 50 were reportedly engaged mostly in writing proposals instead of code.

Consequently, they were an easy target when Spindler needed to cut costs. And in June 1993, the "Star Trek" project was cancelled and no more work was done on that move to Intel.

Steve Jobs returns, and Apple bears down

"It's perfectly technically feasible to port [Mac OS X] Panther to any processor," said Steve Jobs in November 2003. "We're running it on the PowerPC and we're very happy with the PowerPC. We have all the options in the world, but the PowerPC road map looks very strong so we don't have any plans to switch processor families at this point."According to Linzmayer, Jobs said this at an analyst meeting conference call, but beyond that account, we couldn't confirm the quote. If it is accurate, though, then something big changed right after it -- and it's probably to do with that phrase "road map."

Ultimately, Jobs would say the opposite at the launch of the transition to Intel, that PowerPC just didn't have the future Apple needed. Internally, though, Jobs or at least enough key personnel within Apple had been suspecting this for some time.

Around the year 2000, Apple began working on what would become the successful move. "Mac OS X has been leading a secret double life for the past five years," revealed Steve Jobs at the 2005 launch.

"There have been rumors to this effect," he continued, to laughter from a knowing WWDC 2005 audience who may had been reading half a decade's worth of rumors about it on AppleInsider. Jobs showed a slide marking the precise building at Apple's Infinite Loop campus where the work took place. "Right there, we've had teams doing the just-in-case scenario."

"Our rule has been that our designs for OS X must be processor independent," he said. "And that every project must be built for both the PowerPC and Intel processors. So today for the first time, I can confirm the rumors that every release of Mac OS X has been compiled for both PowerPC and Intel. This has been going on for the last five years."

Specifically, it had been going on since the release of Mac OS X Cheetah, which was released to the public on March 21, 2001.

Lessons for ARM

It's no surprise whatsoever that anything Apple does is planned in advance. Even a new Apple Watch band takes some work before it's announced to the public, so a gigantic change such as a move to a new processor is going to take time. It is going to start in secret, too, as Apple has learned that transition projects can go wrong.Those first projects may have failed to move the Mac over to Intel, but once Apple truly committed to doing it, the company worked very quickly and very efficiently. That transition of the entire Mac lineup was incredibly smooth, and that's one reason why we can make some assumptions about the move to ARM.

First, it's been well and probably very long-planned. That's both in terms of the technology -- you can be certain that there are ARM-based Macs in Apple Park right now -- but also in terms of the transition.

What may be the most significant lesson from the Intel move, though, comes in that quote from Steve Jobs. "Our rule has been that our designs for OS X must be processor independent."

Having separated out the operating system so that it could sit atop either PowerPC or Intel, it seems unlikely that Apple will have ever decided to undo that. The current macOS is probably in a similar position and that means it won't need rewriting to work on ARM.

Apps will need work, as we saw in the Intel move, and even before that with the transition to PowerPC. Where the '90s project was a gigantic rewriting of the operating system to get it to work on Intel's processors, Apple has set the table with moves it has made for the last two decades to try and make that migration dramatically easier.

Or at least, easier for Apple. Regardless of the underpinnings of the operating system, it is still going to be the case that developers will shoulder a large burden. That will mean some developers having more complex jobs to do than others.

Users left in the cold with apps that don't make the transition won't benefit. But, the majority of the Mac using base, especially those yet to come, will see big benefits, though.

Keep up with AppleInsider by downloading the AppleInsider app for iOS, and follow us on YouTube, Twitter @appleinsider and Facebook for live, late-breaking coverage. You can also check out our official Instagram account for exclusive photos.

Comments

I understand that running Windows on Mac is your use case, but that is not even remotely a universal one -- and this is addressed in the piece. In regards to "add it as a secondary processor," Apple has already done this for the last four years with the T1 and T2 processors.

And, it's not like your old gear is going to burst into flames, or Apple will renovate the entire product line top to bottom immediately. Windows compatibility will still be around on the "Pro"-level hardware for a while.

Rumors suggest this time that no transition hardware will be provided... Apple is going to jump right in with ARM products. And this raises the question of whether Apple has been able to use the T1 and T2 coprocessors all along to facilitate a complete transition. It still seems a bit risky not to have widespread availability to developers, both internal and external to Apple, of a purely ARM architecture system, though. Perhaps the rumored ARM iMac will only be available to developers at first.

On top of that, Apple has made so many moves with macOS and IDE that the transition should be even more seamless than ever before. How Apple has been using T2 to help prepare for this transition is interesting. Hopefully we see something about that come out if that's the case.

Apple transitioned the entire Mac product line to Intel in about 14 months time from the original announcement of the transition, and in about 7 months time from availability of the first X86 Mac models.

There is simply no economic benefit from having more cores of the same speed. Most applications don't need all cores at full speed. The OS and apps would benefit the most if each app is given low speed cores and apps given high speed cores when performance is demanded.

Why would you want cores that have to be all of the same speed when you can easily have each low speed core to be dedicated for processing a certain task at a much lower clock speed? For example, if you build a core that is dedicated to processing a frame of a video and you decide that you only need say 500 Mhz per frame, it would be so much more economical to have 30 500Mhz cores along with a couple of 4GHz cores for tasks that require more complex calculations than to force all cores to have the same speed which actually degrade performance overall and not cost effective at all.

but now, does Apple have a chip they could put into the iMac Pro? How about the new Mac Pro? We can’t assume they will have one ready for those machines in less than a year, maybe more. Those high level apps need some time to come over. From experience, we know that it will take a year. Even Apple took a lot of time moving FCS and their other high level apps.

Given how big and wealthy Apple is, isn’t it entirely possible that they could keep Intel machines on the market as long as they want, if there is a need? Last time they switched from Motorola to Intel pretty quickly because Motorola wasn’t coming out with chips. Intel will remain in the game for the foreseeable future and will continue making competitive desktop chips I imagine. And if even their desktop chips become uncompetitive, then I don’t think people will miss them so much, will they?

Look at the Ampere Altra server processor announced 3 months ago: 80 64-bit ARM cores, 1 MB L2 cache per core, ECC. Performance often on par with AMD EPYC 7742 (64 core/128 thread). My experience with prosumer versions of the 7742, the Ryzen Threadripper 3970x (32 core) and 3990x (64 core), is that they're far faster than the 28-core Mac Pro. Like 2-3X faster.

The Osborne Effect will also push Apple to complete the transition faster than some might expect. We may also see some Apple ingenuity for maintaining longer term Intel compatibility, too.

I don't see Apple as quick to abandon Intel, particularly in the high end, there's still a worlds of work to be done and compatibility to sort out.

sleight-of-hand, possibly because of Apple's infamous secrecy. But it's SOP

in the industry. (I'm long-retired from participating in such at the defunct Sun Microsystems,

which maintained software builds for SPARC, Intel, PowerPC, and even HP's Itanium.)

Some of the transition stuff is motivated by contractual obligations.

I believe for Motorola/IBM they had a 15-or-20 year exclusive arrangement to use just that architecture.

Steve Jobs analogized it to a marriage contract. Maybe they had something similar for

Intel -- I vaguely recall details (partly-redacted) which show up in SEC documents.

So when the exclusivity ends, and either the vendor has fallen behind the competition,

or you are allowed to roll-your-own, it's always wise to have a Plan B lined up

beforehand.

Aside: yes you can certainly get a divorce mid-stream at a cost. Tesla did this due to a rift

with Mobileye, and their transition to Nvidia served them until they could vertically integrate better.

https://www.anandtech.com/show/15841/intel-discloses-lakefield-cpus-specifications-64-execution-units-up-to-30-ghz-7-w

Seriously, though, There's already an ARM processor in all the new Macs, and the central thing I've been talking about is that the T-Series processor will take over more and more of the OS operations, leaving the x86 just for heavy lifting, leading ultimately to completely removing the x86 at some point in the future. Whether they go to x86 emulation for legacy support, or my fanciful idea of selling back end processing as a service, or just cutting the cord completely is less clear.

One thing is, if they do axe x86 support completely, it could open up a market for consumer level Cloud Compute services, whether from Apple or someone else. You just rent time on an x86 VM (or software container, even) to run your Windows, or even legacy Mac software. Admittedly, this is less convenient for people when not connected to the net, but for a lot of users, like myself, who mainly use Windows in situations that already require a network connection, it would do.