AppleInsider · Kasper's Automated Slave

About

- Username

- AppleInsider

- Joined

- Visits

- 52

- Last Active

- Roles

- administrator

- Points

- 10,707

- Badges

- 1

- Posts

- 66,634

Reactions

-

EU may be reassessing billion-dollar Big Tech fines as it waits for Trump

All the impending EU fines and rulings against Apple, Google, and Meta, are reportedly off the table as Europe awaits Trump -- and reveals just how political its regulations are.

The EU has reportedly paused its probes into Big Tech issues such as Apple's App Store rules

For ten years, the European Union and especially competition chief Margrethe Vestager, has been working to control Big Tech. It's done so mostly very successfully, with the region being the first to implement a Digital Markets Act (DMA) that laid out conditions -- and especially potential fines for transgressions.

Now according to the Financial Times, however, all of the regulator's plans for fines are on hold. Only what is described as technical work will continue on any of the Big Tech investigations, and for the moment there will be no fines.

It's because the main EU chiefs responsible have reached their term limits and are leaving. And it's surely because the incoming Trump Administration in the US is expected to listen to Big Tech lobbyists and push back against regulation.

"It's going to be a whole new ballgame with these tech oligarchs so close to Trump and using that to pressurise us," an unnamed senior EU diplomat said. "So much is up in the air right now."

Reportedly, two further EU officials said that regulators in Brussels were now waiting for political direction. Until they get that guidance, they will not be making their final decisions on cases such as those against Apple, Google, and Meta.

However, these comments have been denied by the European Union. "There is no delay in finalising the opened non-compliance cases, and especially not due to any political considerations," said an EU spokesperson.

Yet EU lawmakers such as MEP Stephanie Yon-Courtin have been pressing the regulators to continue, because the DMA "cannot be taken hostage" because of political or diplomatic reasons.

Yon-Courtin was among those involved in the original drafting of the EU regulations. She has asked the European Commission's president to "reassure me that your cabinet and yourself are fully supporting the effective implementation of the DMA, without further delay."The EU and Apple

The EU was not shy about enforcing the DMA during Vestager's tenure, nor of imposing fines. In March 2024, it fined Apple $2 billion for anticompetitive practice with Apple Music -- despite Apple's streaming service being far from dominant.

It's decisions were controversial, then, and sometimes nonsensical. Plus Vestager has been swift to lambast Apple over any perceived slight against the EU.

Vestager has been successful, at least in the eyes of the EU. As well as getting is 27 member states to pass the DMA into law, it's because of the EU that Apple's iPhone switched to using USB-C for charging.

Plus it is because of the EU that Apple was forced to pay Ireland $14 billion in back taxes -- despite even Ireland saying it was wrong.

Apple may well have made that USB-C switch anyway, but it wouldn't have been with the iPhone 15 range in 2023. And Apple would never have even considered allowing third-party app stores -- and has unsuccessfully fought against them.

While Apple appears to have followed EU regulations with practically surgical precision, its rivals have described it as doing so with malicious compliance. Epic Games said Apple's EU concessions were "hot garbage."

Consequently, by June 2024, it was expected that the EU would fine Apple over its alleged failure to comply with the DMA. That appears to be one of the decisions that has been put on hold, and perhaps more because of EU administration changes than America's.

Margrethe Vestager is being replaced as Executive Vice-President of the European Commission

For in August 2024, it was announced that Margrethe Vestager would not be getting a third term as European Commissioner for Competition. She'd already publicly predicted she would be out of the role, though, so possibly decisions were already being delayed pending the changes.What happens next

The European Union has easily been the most successful territory in imposing regulations over Big Tech, but everywhere from India to the US is working to do the same. The pressure on Apple to open up its systems is ultimately going to continue, then.

But the fact that fines, investigations, and decisions, are all being paused points to just how much regulations are really political decisions. Tim Cook has already described some of the EU's decisions as "total political crap," and it looks like he's right.

The politics will not end, however, even as the EU is said to be reviewing its processes. For as the EU pauses, Big Tech is cozying up to incoming President Trump in order to get political might on its side.

It's likely, then, that Big Tech firms will see less impact from regulation for the period of the next administration.

Whether or not that's good for consumers, though, will be irrelevant. While all sides, doubtlessly including Apple, will proclaim that they only want to protect users, this is going to be a fight between governments and Big Tech.

Or rather, it's going to continue to be. For all that it should be applauded for being the first territory to successfully implement a Digital Markets Act, the EU's decisions have favored companies over consumers.

The EU would deny that, and it has repeatedly insisted that it is working to protect users. But as its fine against Apple Music showed, the EU has continually and even unreasonably favored Spotify, a firm based in its territory.

Read on AppleInsider

-

Next generation CarPlay is missing in action as Apple fails to hit its own deadline

Back in 2022, Apple loudly talked up its next-generation CarPlay before quietly committing to it being released in 2024 -- and now it's saying nothing about having missed that deadline.

The new CarPlay would take over all car information and entertainment functions -- image credit: Apple

Apple has always had a reputation for refusing to announce or even admit to something it was working on, until it was ready to ship. Yet when it gave what it called a sneak peek at the new CarPlay in 2022, it sounded as if it were ready.

"Automakers from around the world are excited to bring this new vision of CarPlay to customers," said Emily Schubert, Apple's Senior Manager of Car Experience Engineering at WWDC 2022. "Vehicles will start to be announced late next year, and we can't wait to show you more further down the road."

What Apple showed was nothing less than the complete takeover of a car's entire dashboard by CarPlay. Instead of being confined to a square-ish screen that shows a few apps, the new CarPlay runs everything.

The speed display, the rev counter, the trip counter, whether the car was in Drive or Park, everything. The new CarPlay would use every screen in the car -- and be adapted so that "no matter what type of unique screen shapes or layouts you may have, this next generation of CarPlay feels like it was made specifically for your car."

Schubert is a 20-year veteran of Apple, and in October 2023, she was promoted to Director, Car Experience. But while she is presumably plugging away at the new CarPlay, those excited automakers don't appear to be.

Apple showed a slide featuring 14 car manufacturers, from Audi to Volvo, and none of them have released a car featuring the new CarPlay.

To be fair to Schubert, her three-minute WWDC speech only committed Apple to how cars would start to be announced in 2023, and she wasn't wrong. In 2023, both Porsche and Aston Martin showed off what were basically concept designs.

However, they did so simultaneously on December 20, 2023 -- and neither has actually released a car. Aston Martin committed to a 2024 launch, but Porsche wouldn't be drawn on any date.

And if Apple's WWDC announcement was also carefully-worded, Apple's website announcement was not. "First models arrive in 2024," it said.

The key phrase is at the bottom -- "First models arrive in 2024" -- image credit: Apple

At time of writing, it still says that.Money doesn't solve everything

It's easy to say that Apple has so much money that it can throw at any problem, but there are limits to even its resources. There are limits when you're working with any outside firms, let alone 14 of them, for which your CarPlay project may not be a priority.

Then it's surely not an easy task to have an iPhone communicate "with your vehicle's real-time systems in an on-device, privacy-friendly way, showing all of your driving information, like speed, RPMs, fuel level, temperature, and more," as Schubert said.

It's just unusual that Apple would either announce a major release early, or that it would fail to correctly assess how long the project would take. There was speculation in 2022 that the announcement was really made because car manufacturers appeared to be abandoning support for CarPlay.

Schubert also said in her speech that "79% of US buyers would only consider a car that works with CarPlay," which did definitely sound like a shot across the bows of car makers thinking of leaving.

Some still did, though it's not been a great or popular move for those manufacturers.

There was also speculation that this new CarPlay was actually a sneak peek at the Apple Car -- but the car project was then abandoned.

Maybe CarPlay has been abandoned too, although there have been signs of its life in regulatory databases.We've been here before, on a smaller scale

Or maybe it's just a larger-scale version of what happened with Apple Music over its classical music app. Apple specifically promised that Apple Music Classical would be released in 2022, after the company acquired classical streamer Primephonic in 2021.

While it missed its 2022 deadline, Apple Music Classical was also constantly rumored to be about to launch. There was also evidence, too, in the form of code in iOS.

In the end, Apple Music Classical came out as practically a surprise, a few months into 2023. It's still been a long rollout to different Apple devices, although most recently it was made available -- on CarPlay.

The new CarPlay could go the same way. But unlike Apple Music Classical, its fate is not entirely within Apple's control.

Instead, it depends on Apple and at least 14 major car manufacturers.

Read on AppleInsider

-

Keychron Q5 HE review: Marvelously magnetic mechanical keyboard

The Keychron Q5 HE is a great mechanical keyboard that proves that magnetic switches are useful for more than gaming.

Keychron Q5 HE review

HE keyboards are a great upgrade for typists and gamers for their durability, precision, and customizability.

The HE stands for Hall Effect, which describes part of how magnets influence electric charge. This finds its way into keyboards when manufacturers put magnets into the switches and use this effect to sense when a key is pressed much more accurately than an analog mechanical switch.

The technology took the keyboard community by storm this year. It provides a great advantage to gaming, as you can customize your key actuation with absolute precision through software.

Over the summer, HE keyboards stirred up significant controversy within the Counter-Strike 2 community. This controversy led to their ban in tournaments due to features such as magnetic switches' being able to trigger different inputs at different points of actuation during the key press.

Despite this, HE keyboards still provide several advantages for everyone, including faster response times and reduced wear on the switches.

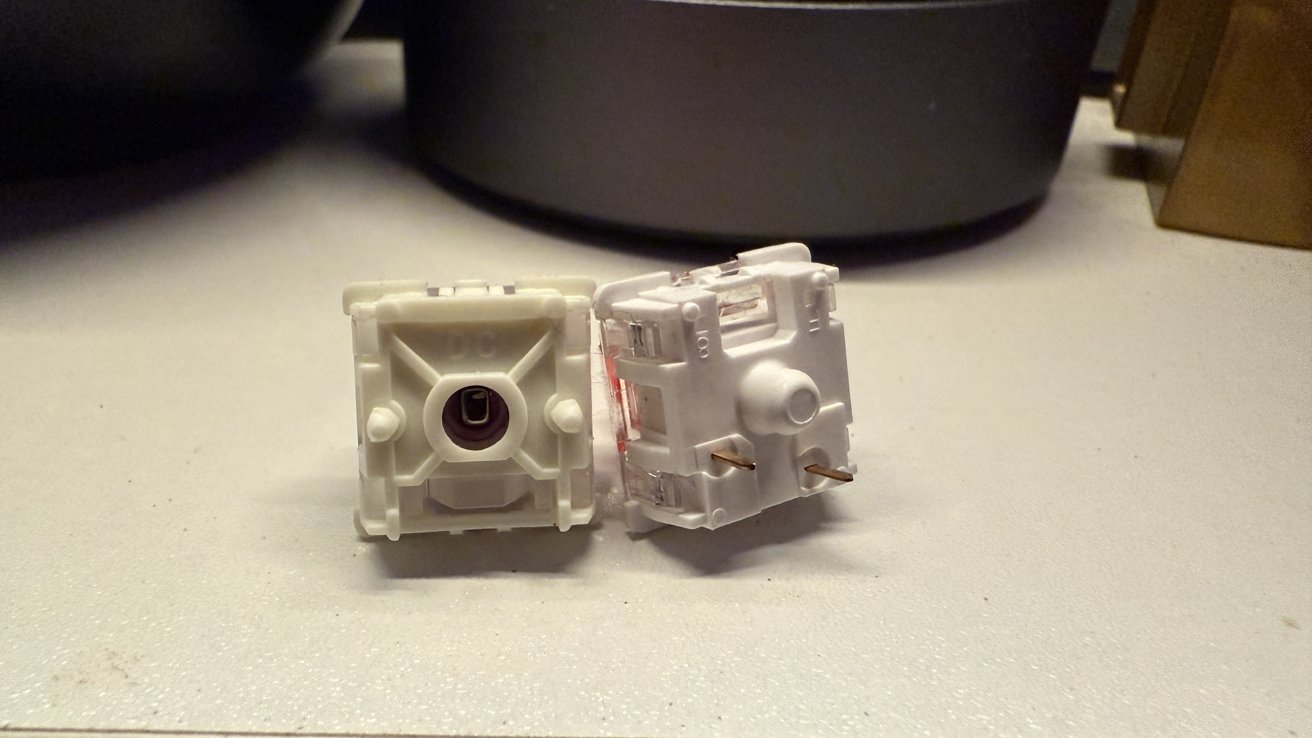

Keychron Q5 HE review: Gateron Nebula switch on the left, Keychron K Pro Red on the right. You can see the magnet inside the Nebula switch.Keychron Q5 HE - Design

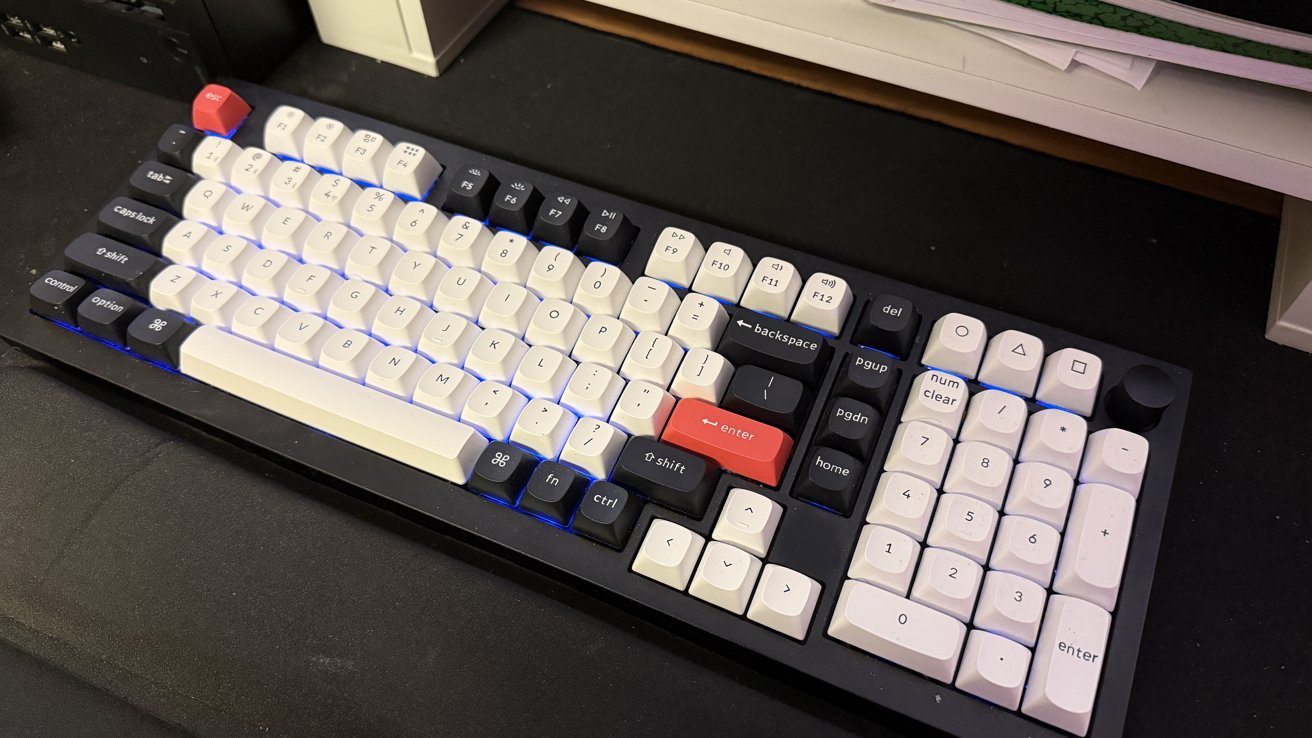

The Keychron Q5 HE and the Q5 Pro have a lot of similarities; they both have all-metal bodies, knobs, RGB, and customization through software and hot-swapping.

But that's where the similarities end. The Q5 HE has different keycaps, magnetic switches, and compatibility with the Keychron launcher.

Keychron Q5 HE review: Switches on the back for OS and connectivity.

You can fully customize the Q5 HE from the ground up on website.

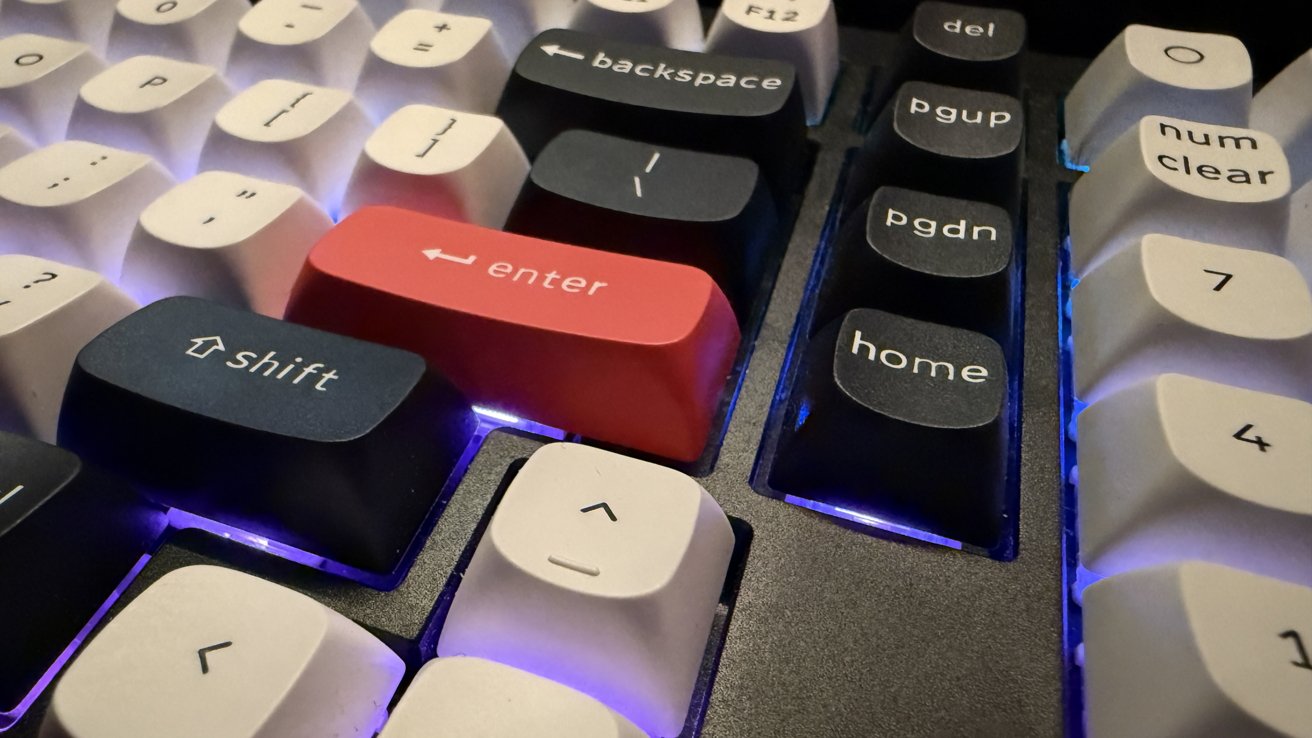

The keycaps are "OSA" - OEM spherical angled. It seems keyboard specs are full of acronyms, but OEM-type keys are taller in the back of the keyboard and shorter in the front. It's nothing unorthodox, and it's quite comfortable on the fingertips.

The pre-assembled version comes with the Nebula Gateron double-rail magnetic switch. The Dawn and Aurora versions are available to buy, having different starting and ending forces.

Keychron's Launcher web app goes a long way in managing mapping your keys, requiring Chrome/Opera/Edge for your browser. It has a new update for their HE keyboards, allowing you to manually set the actuation distance for each key.

Keychron Q5 HE review: The HE menu of Keychron Launcher.

You can assign multiple actions to one key depending on the depth of your keystroke since the actuation distance can be quantified so accurately. This adds a whole new dimension to macros and shortcuts.

For example, you could make a half-press on the backspace to delete the last character, but a full press could be a macro to delete the previous word or line. These advantages of HE go beyond just gaming.Keychron Q5 HE - Specs

Product Detail

Spec

Keycap

OSA Double-shot keycaps, not shine-through

MCU

ARM Cortex-M4 32-bit STM32F402RC (256KB Flash)

Backlight

South-facing RGB LED

Switch

Gateron double-rail magnetic switch

Hot-swappable Support

Yes, compatible with Gateron double-rail magnetic switch only.

Stabilizer

Screw-in PCB stabilizer

Cable

Type-C cable (1.8 m) + Type-A to Type-C adapter

Connectivity

2.4 GHz / Bluetooth / Type-C wired

Bluetooth Version

5.2

Battery

4000 mAh Rechargeable li-polymer battery

Operating Environment

-10 to 50

Wireless Working Time (Backlit off)

Up to 100 hours

Weight

2187 g 10 g (Fully Assembled version)

Body Material

Aluminum

Plate Material

Aluminum

Polling Rate

1000 Hz (Wired and 2.4 GHz) / 90Hz (Bluetooth)

Keychron Q5 HE - Use

First off, the typing experience on the Gateron Nebula switches is extremely smooth. You can feel the difference between a magnetic and mechanical keyboard in that less material (no springs and fewer mechanical parts) is pushed into the board, giving a lighter feel.

The magnetic keys activate precisely upon pressing and deactivate when you release, which allows for an immediate repetition of keystrokes, making the reset faster than traditional mechanical switches. This technically will enable you to "type faster" if you do several of the same input in succession, which is largely useful for those who game, code, or use macros for anything.

Keychron Q5 HE review: Closeup of the Gateron Double-Rail Magentic Nebula Switch.

At around 5 pounds (2187 g) fully assembled, the Q5 model is a semi-permanent block of aluminum on your desk, making it not so portable.

As with most Keychron keyboards in this price range, you can connect to up to three devices via Bluetooth, allowing you to use the Q5 HE to switch between your Mac, iPhone, and iPad. This also works well with the Windows/Mac switch on the back, so you can pair both to bring out the gaming advantage of HE keyboards on your PC.

To pair, press fn+1, 2, or 3 and hold for four seconds to connect to a new device, lightly press fn and the number for your device to switch to that specific one.

The latency on the Q5 HE is extremely low as well, as a processor is embedded in the case for a 1000 Hz polling rate while wired and wireless with a 2.4 GHz wireless connection and Bluetooth 5.2.

Keychron Q5 HE review: 96% layout with an aluminum body takes up a bit of space.Keychron Q5 HE - Hall Effect can be for everyone

HE keyboards have become infamous for their ability to provide faster responses to time-sensitive tasks like competitive games, but they're also just fun to use for daily life. People use their keyboards to work and play hard, so it's the best of both worlds to have something to give you an edge inside a durable chassis.

Keychron has a reliable formula for their keyboards in this price range, emphasizing customization, durability, and quality of switches. The Q5 HE checks off all these boxes and may be one of the easiest ways for a Mac user to enjoy an HE keyboard.

Keychron Q5 HE review: Closeup of the keys.Keychron Q5 HE Pros

- Hardware and software make the most of magnetic switches

- 1000 Hz polling wired or wireless

- Durable, reliable keyboard

Keychron Q5 HE Cons

- Controversial for competitive gaming

- Needs customization to get the most out of it, not for everyone

Rating: 4 out of 5

Where to buy the Keychron Q5 HE

The Keychron Q5 HE is available on Amazon for $249.99, and the Keychron store for $229.00.

Read on AppleInsider

-

iPhone case maker Zagg hit with big customer credit card number theft

Consumer electronics and iPhone accessory maker Zagg is letting customers know that credit card transactions may have been compromised due to a hack of a third-party payment processor.

Zagg's customer information has been compromised via a third-party hack.

Zagg, based in Utah, makes products such as keyboards, phone cases, screen protectors, power banks, and other accessories. It uses BigCommerce to process credit card transactions on its website, which also provides an app called FreshClicks for creating commerce-friendly websites.

It was discovered that an attacker was able to breach the FreshClicks app, injecting malicious code that stole customers' card details, reports BeepingComputer.

Letters sent to Zagg customers explained that an "unknown actor" had injected malicious code into the FreshClick app, designed to scrape credit card data entered as part of the Zagg checkout process. This took place between October 26 and November 7.

The breach was reported to regulators and federal authorities. While the number of affected customers is unreported, the attackers managed to steal names, addresses, and payment card data of customers.

Affected customers were told via the letter to monitor their financial account activity, including adding fraud alerts and a credit freeze. Customers of Zagg who might have had their card details compromised will have their card activity monitored for 12 months via Experian at no charge. .

In a statement, Big Commerce insisted its own systems were not breached or compromised. However, once the problem was discovered, BigCommerce disabled and uninstalled FreshClicks from its clients' stores, which removed compromised APIs and malicious code.

Read on AppleInsider

-

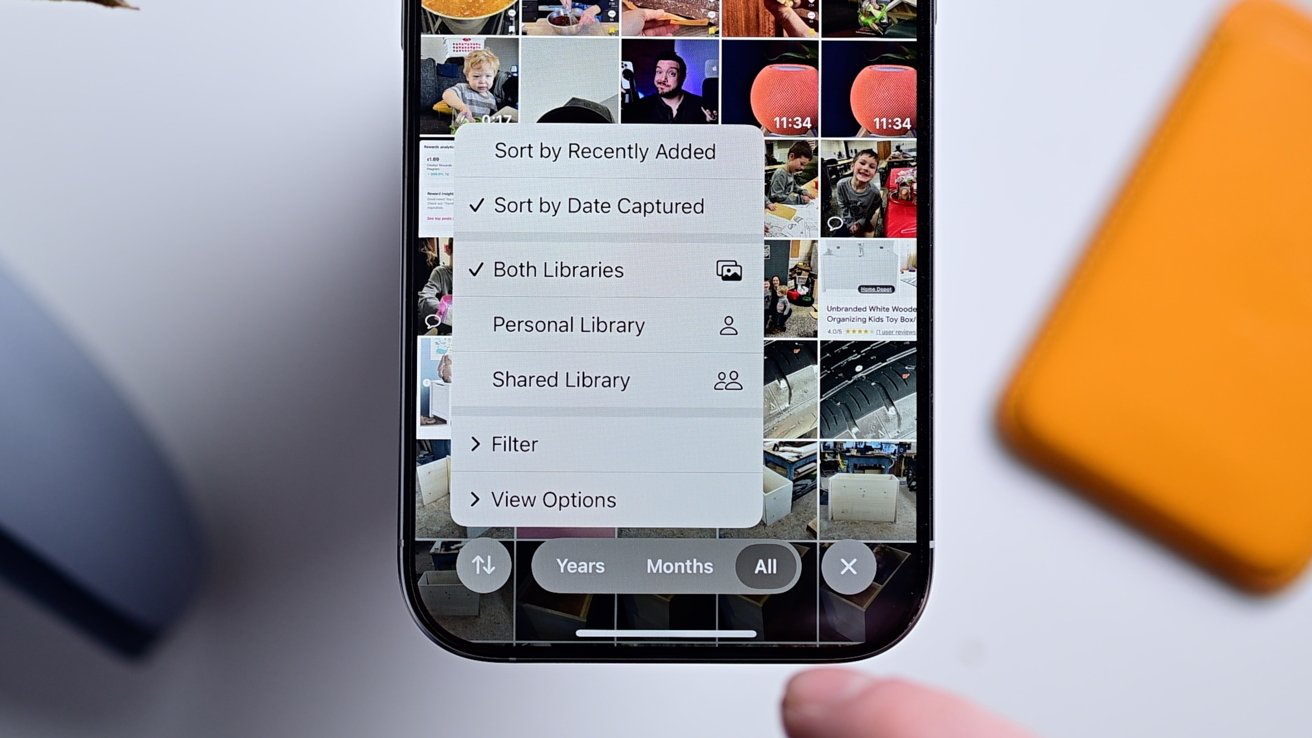

How to make iOS 18 Photos work more like it used to

Based on what we've seen, odds are good that you're not in love with the redesigned Photos app in iOS 18. While the old version isn't returning, here's how to make it more like its beloved former self.

Here's how to make the iOS 18 Photos app better

With iOS 18, Apple undertook the daunting task of redesigning the Photos app. While the app was loved by many, it hadn't changed in a while and Apple wanted to prep it for the future.

This modernization didn't go over well. The redesign decision has been a controversial to say the least.

The new Photos app compared to the old one on the right

Even months after launch, many users complain of confusing design, missing features, and a general dislike of the app.

The old version isn't coming back. There are some things you can do to restore your Photos experience closer to what you had, though.How to fix the Photos app in iOS 18

The new app has a singular interface, ditching the tabs. Scroll up to see your full gallery and down to see various collections of images and videos.

Adjust the gallery view to show recents

The first thing you can do is adjust the gallery view.- Tap the up/down arrows in the lower-left corner

- Instead of sorting by "Date captured," sort by "Recently added" so you see all your new images first

- We'd also recommend considering showing screenshots in this gallery view too

That will allow you to see all your images, as they're added, including the screenshots. There are other options there too you can explore that may make sense for you.

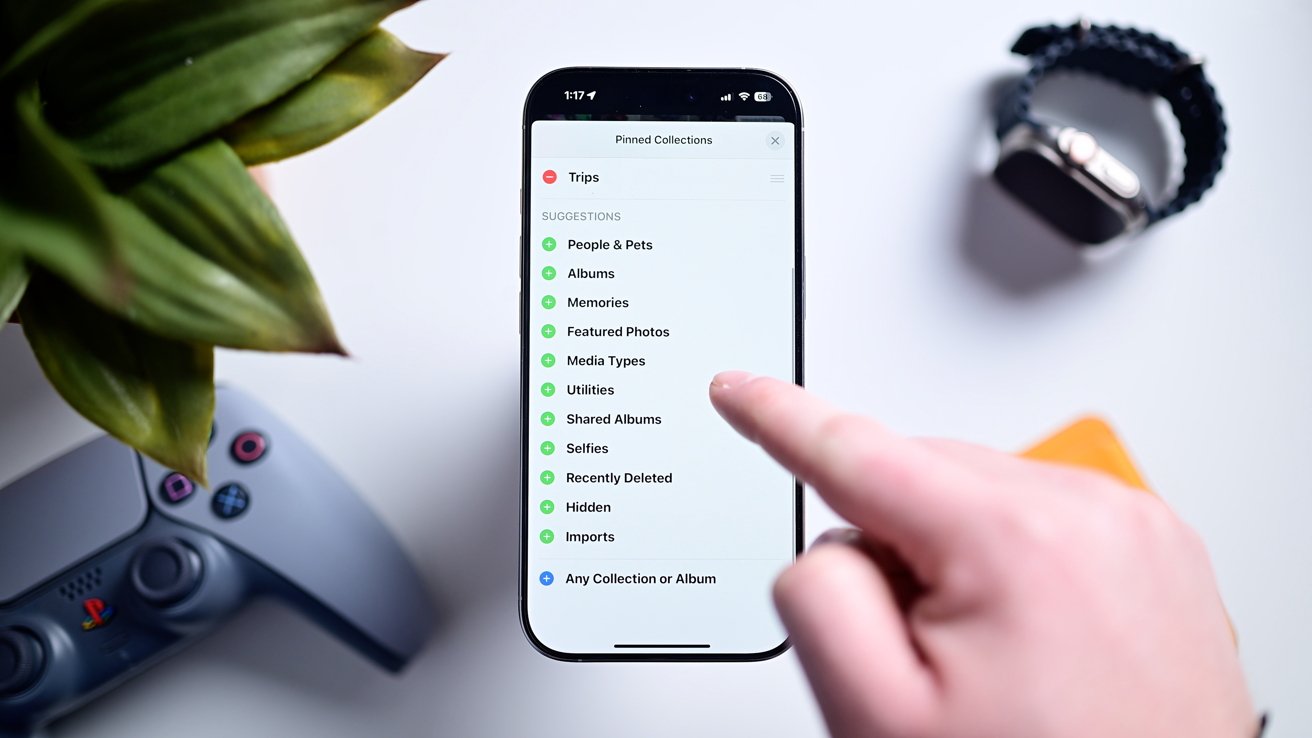

Hide and reorder sections in the Photos app

The next option is to remove the unnecessary sections of the app.- Scroll to the bottom of the Photos app

- Tap the large "Customize & Reorder" button. Apple really wants to make sure you see this!

- Uncheck any of the sections that you don't want to see in the Photos app

- We'd suggest hiding Featured Photos, Recent Days, and Wallpapers to start

- You can also reorder the sections by tapping, holding, and dragging on the right side of each section while in this edit view

- Tap "Done"

One of the ways that we found to vastly improve the usability was a reliance on the Pinned Collections section. It's a new category that lets the user decide what is shown there.

Add collections to the pinned view- Make sure Pinned Collections is enabled in the edit view outlined above

- Tap Modify on the right side of the section in the Photos app

- Tap the + button on any collection you'd like to add and the - on any section you'd like to remove

- Below the list of suggestions, you an tap + Any Collection or Album

- This gives you 100% control on anything you'd like to add from a gallery of you, your partner, and kids, all of your screenshots, your hidden photos, and more.

Apple has been listening to user feedback

As hard as it is to believe sometimes, Apple does listen to user feedback and we've seen this quite a bit with the redesigned Photos app.

The old featured carousel was axed before release

During the original iOS 18 beta phase, Apple took a drastic step of parring back its ambitious design and removing features, like the cycling carousel at the top. All based on feedback it received.

As we mentioned, iOS 18.2 also added more quality of life improvements and changes.

When viewing a collection, you can now swipe to go back to the main view versus forced to tap the arrow in the top-left corner.

And, videos immediately play full screen with just a tap to dismiss the controls, just like before.

Videos can be scrubbed frame by frame once again. Plus, you can view the scrubbing time on a nanosecond-level in the timeline.

Hide preview videos

When viewing any collection, there is a movie preview playing at the top. With iOS 18.2, this can be disable to show a standard gallery view.

If you have more suggestions, you can also file feedback with Apple. Just visit feedback.apple.com and let them know.

The change has definitely been a drastic one, and making it better requires a little bit of time, but it's getting better. You just have to give it a chance.

Read on AppleInsider